x

Contents

Home

Home

Home

Foreword:

The Apparatus of Attraction

by Gregory L. Ulmer

Rhizcomics begins with some navigation instructions, to help us find our way around this hybrid text, appropriate for a helmsman (cybernaut). This signature effect encourages me in my inclination to compose mystorically, to personalize and situate our position in the transition from literacy to electracy. The image emblematizes my theme, beginning with the scene of a beach in Florida, not far from where I professed electracy from 1972 to 2015. Those designations, concerning deixis, “you” and “here,” not to mention the copula, have metaphysical import. Beyond GPS is EPS (Existential Positioning System), the latter being the concern of electracy. “Grammatology” is the disciplinary orientation, the history and theory of writing, écriture, understood in the broadest possible terms, as articulated by Jacques Derrida in Of Grammatology. The emblem includes a rebus, referencing the origins of writing in ancient Sumerian, an example of phonetic elements introduced into inscription. Exploiting the homophone associating “life” (til) with “arrow” (ti), the Sumerians wrote “life” with the “arrow” shape. As we know from Freud, Lacan, and psychoanalytic theory, our dreams signify in this mode of logograms, (letter), and this work of dreams describes something happening in digital media as well, having to do with trace as vectoral force of life/death.

This foreword is a vector, carrying the project of apparatus invention to the next generation. It is an opportunity to review the past four decades or so of invention, localized in one exchange among others, between Ulmer and Helms. Derrida authorizes signature address, so we could say that the apple has not fallen far from the tree, die Ulme of elm tree in German Ulmer, the “elm” in Helms. It reminds me that Albert Einstein was born in Ulm, Germany (1879). Einstein is the emblematic genius of the twentieth century, the prototype of the image of wide scope formulated by Gerald Holton, that is central to electrate pedagogy developed during my career, mentioned here to signal a dispositio of pattern rather than argument.

How far have we progressed in forty years, from one elm to another? One measure is the shift of theoretical focus from Derrida in Applied Grammatology (1985) to Lyotard in Rhizcomics. I encountered Derrida’s De la grammatologie in a bookstore in Boston, 1970, while still a graduate student writing a dissertation on Rousseau. Rousseau was the go-between. As an early adopter of Derrida, I was more interested in “grammatology” than deconstruction, and so I took what turned out to be the back road to far towns. The shortest distance between Ulmer and Helms is whatever separates Derrida’s grammatology from Jean-François Lyotard’s figural. As Helms explains, Discourse, Figure is in conversation with Of Grammatology, regarding difference, differance, and especially grammè (line, trace). The term “electracy” is a portmanteau, combining “electricity” (the energy of digital civilization) with “trace” (representing Derrida’s family of terms, of which the best known is “differance”). The point is that the theoretical argument of Rhizcomics focuses on a question fundamental to the invention of electracy as the apparatus of digital technology, and advances it appropriately to accommodate new considerations, which is to say that it is a work of grammatology. These classics of French poststructuralism remain relevant, with much still to teach us. Helms through Lyotard brings out a dimension of trace concerned with writing beyond language, in the mode of drawing, using the “figural” to account for a rhetoric of text-image hyper-reflection in general, as manifested in comics specifically. Helms is starting out from more or less where I am leaving off: he returns to trace as the electrate equivalent of sign in literacy, but shifts attention to signification beyond linguistics supported in “multimodality,” theorized in Applied Grammatology through Derrida’s picto-ideo-phonographic writing.

If we measure just how far we have come in the passage from literacy to electracy strictly in terms of the theory, the philosophical invention of the metaphysics of apparatus, then it might seem that the apple has not rolled that far, moving between these early poststructuralists, Derrida and Lyotard (and despite the title, Lyotard is the chief advisor for this experiment), except to say that Helms knows and is addressing the fundamental question of digital metaphysics: the shift from sign to trace. If we were constructing a heuretic CATTt for Rhizcomics, French poststructuralism in general supplies the theory resource. There is good reason to feature Deleuze in the rhizome allusion, but the first consideration is to notice the argument, unpacking the theoretical rationale for comics as a mode of inquiry. One purpose of this foreword is to foreground this rationale, to frame the disciplinary focus of Rhizcomics in apparatus theory, addressing rhetoric and composition, computers and writing, digital humanities, and related academic disciplines, to feature what is at stake in the experiment for the coming education. Trace is the most important question challenging our disciplines today.

When I first met Jason Helms he was still a graduate student in the RCID (Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design) program of Clemson University, under the direction of Victor Vitanza. That he was already familiar with electracy and versed in theory was due to this affiliation, given the close association between Vitanza and Ulmer, the Arlington and Florida Schools, as they are sometimes identified. It took me some time to find the target of my own CATTt, and in fact it found me, in the person of Victor Vitanza, beginning around the time of Teletheory (1989). I was blessed in my career with numerous superb students, extended vicariously through Vitanza’s students, including those now inventing in Clemson RCID. Helms and I went for coffee where I learned two things that sparked a sense of optimism about the coming education. First, at some point along the way to his master’s degree, Helms learned enough Classical Greek to compose his own translations of key passages by the Pre-Socratics, among others, useful for engagement with Heidegger’s inventive etymologies. Helms, in other words, is a primary grammatologist, including the likes of Eric Havelock among others upon whom I depend for the history of transition from orality to literacy. Havelock argues that the first concept was “Justice,” invented by Plato in the Republic, and that “selfhood” as identity experience and its collective politics of the democratic state are as much an invention of literacy as are alphabetic writing (technology) and school as institution (the Academy).

These are the terms of apparatus creation that set the frame guiding the reformation of education for electracy: technology, institution, identity. Grammatology as disciplinary methodology invents by analogy. We learn from the likes of Havelock, Walter Ong, Jack Goody, Marshall McLuhan, the historical details of the transition from orality to literacy, from which is extracted a template to be mapped in turn on our own condition, to discern the transformation in progress and the sites of opportunity at which an apparatus is open to invention. Derrida connects this English scholarship with French theory through his association with Tel Quel and the development of apparatus (dispositif) in that context, against technological determinism. French apparatus theory proposed that our technologies are social machines, or desiring machines as Deleuze and Guattari clarify: part ideological, part technological, combining into an assemblage according to the dynamics of a bachelor machine, syncretizing “unrelated” components. Here is a principal instruction regarding the contribution our disciplines may make to the coming education: an apparatus is invented from several distinct traditions, not only through technological innovation. Its character is emergent, not predetermined.

STEM disciplines are responsible for one of three registers of electracy only (the digital equipment). The invention of institutional practices (metaphysics) comes from elsewhere. Plato, Aristotle, and their schools did not invent the medium of writing, they invented the rhetoric, logic, method, everything that we still teach today through our textbooks, and that remains fundamental to literacy. The motto of grammatology comes from the poet, Basho: not to follow in the footsteps of the masters, but to seek what they sought. The authoring practices of a digital apparatus are not merely extrapolated from the affordances of the equipment, and even less from imitation of methods of the natural and social sciences. Science is the great achievement of literacy, and will remain metaphysically literate even as it adapts to electracy, just as religion remained metaphysically oral, even as it adapted to the civilization of the book. Changing equipment does not transform metaphysics, nor is there any apparatus free of metaphysics.

The theme of “modality” arises at this point, requiring some disambiguation, given the choral potential of “mode.” At the level of metaphysics there is a fundamental commitment to a particular orientation to reality structuring all institutions of a civilization. It is important to note this orientation in considering heuretics for inventing electracy, keeping in mind the first principle of creativity, which is to be other than what already is given. Electracy is not literacy or orality, across the board. Aristotle in inventing propositional logic focused on the declarative statement, essentially descriptive, capable of being proven true or false. This reduction continued through to modern logic, to Frege and Husserl’s phenomenology. Everything else is rhetoric, in that what counts as real in literate metaphysics is in the order of true-false, which is the origins of science as we know it. The bachelor machine producing the computer begins here, in Aristotle’s truth tables, the syllogism, his discovery of the principle of noncontradiction or excluded middle in the grammar of written Greek. Leibniz supplied the binary number system (0/1), and finally Tesla invented the logic gate. Lautréamont’s bachelor machine established the slots for heuretics as a logic of invention: the meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table. The Wright brothers’ airplane, to cite an example of the pattern, is the meeting of a bicycle wheel and an internal combustion engine in a box kite. The computer results from the meeting of binary numbers and a logic gate in a truth table, in the context of electricity.

One of the paradoxes inherent in apparatus shift is the bootstrapping effect of technical invention: oral people invented writing. The societies that adopted writing used it as part of a metaphysical transformation. Science was invented in a Classical civilization that was oral, religious, tribal in its metaphysics. Electracy dates from the beginning of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. We are familiar with the impact of photography, telegraphy, phonography, and the like as new recording technologies, and we may include the computer as equipment doing for true-false logic what the alphabet did for spoken Greek, or the camera for painting. The computer calculates true-false logic at the speed of light. In this context we may see that however much computation continues to function within the metaphysics of science, it also serves entirely other purposes for which our disciplines have important responsibility. Grammatology shows us where to look for the template, but for now I want to include some scholarship (apologies) to support Helms’s engagement with French theory and Classical Greek, in order to foreground exactly the distinctive character of electrate metaphysics. The example concerns a fundamental pivotal moment for the invention of electracy, in an essay in which Heidegger names the operative orientation, the modality, of electracy, which is not the right-wrong of orality nor the true-false of literacy.

Heidegger’s method of Destruktion is to return to the writings of the Pre-Socratics, as providing a clue to the original experience of Being at the beginnings of literacy. The case most immediately relevant is Heidegger’s translation and commentary on the one surviving fragment by Anaximander. This discussion defines precisely the fundamental turn and return guiding the design of electrate Justice, as the site of bootstrapping a new metaphysics. The standard translation of the fragment is: “according to necessity; for they pay one another recompense and penalty for their injustice” (Heidegger, Early Greek Thinking). Heidegger adds his own translation, based on a careful assessment of each word, in order to bring out the potential of the other beginning: “along the lines of usage; for they let order and thereby also reck belong to one another (in the surmounting) of disorder.”

Heidegger’s other beginning (seeking an alternative to the forgetting of Being that occurred in the Schools) focuses on the experience of Phusis as an emergence from the hidden (unconcealment), shifting away from Plato’s Techne and Logos (craft and plan). Heidegger poses a different question that does not depend on building or looking, but rather that which concerns limit, and here is the opening toward an alternative metaphysics. Entelechy was the term Aristotle coined to name the immanent relationship of form and matter, of actuality (energeia) developing out of potentiality (dunamis). Aristotle interpreted Plato’s question about the relationship between Being and Becoming (of permanence and change) in terms of biological development: an acorn becomes what it is over time (an oak). There is an internal limit; an entity holds itself in its ending. This end (purpose, final cause) is present in its idea, in what it looks like (it has a face). Substance is what is available for view or action in an object (the categories). Heidegger’s focus is rather on the original power of emergence, the force of Being that is not a thing but a process of relation. The issue is not correctness (true or false), but apprehension or experience of being. The emphasis is not on the permanent or eternal, nor that which persists through all change, but rather precisely on the transcience of matter, the arriving and departing, ebb and flow, birth and death: in short, time. Heidegger learned from Aristotle that there is more than one way to say Being, and poetry (arts) offers another kind of relation, another way to understand ordering, of how parts gather and separate, converge and disperse, come into appearance and disappear again. His test case is not biological growth but the art of tragedy, and the limit that it dramatizes, specifically the strangeness of human encounter with the Overpowering (called Deinon), the fundamental limit of finitude, mortality, disaster, death. Human beings are uncanny, inherently exiled from hearth and home, in confrontation with the irreducible aporia—death—as we learn from the destiny of Antigone.

Heidegger’s method adheres to literate metaphysics in recognizing that ontology—the science of being—is a capability of alphabetic writing. His turn to poetry as the model of inquiry liberates him from the jurisprudence of “category” (“indictment” in Greek), to exploit polysemy rather than definition as a resource for thinking. He examines the term Deinon and finds two senses with respect to confrontation. One involves Techne as a violence of laying down a way or path, and that is the way taken by literacy. The second sense is the source of Heidegger’s innovation, establishing the basis for creating a new Justice. This other power is revealed in the German term Fug: der Fug (what is fitting, just, right); die Fuge (joint, seam, gap, space, suture); fugen (to join, fit together). One says, Die Zeit ist aus den fugen (the times are out of joint). Figurative usage of the verb fügen gives “fitting arrangement” explicitly concerning justice. There is even the homonym “fugue,” referring to the musical form, relevant as a figure of counterpoint in this context. Heidegger developed this semantic field relative to “injustice” and “necessity” in Anaximander’s fragment. Heidegger unpacks Fug relative to Justice (Dike) as jointing, jointure, a framework (set-up) determining what is fitting, thus merging the two senses (Techne, Dike): confronting the Overpowering, men search for order (Fug) yet cannot master it. The Overpowering requires a place, a scene of disclosure. This scene of joining and breaking is humanity itself: Dasein (there-being). In his later period Heidegger shifted the point of view of this breach from individual to collective, replacing Dasein with Ereignis (Event). Man (humankind) is a breach into which and through which being bursts forth to appear as event (not thing) (Janicaud, Heidegger from Metaphysics to Thought). This account approaches well-being from the side of aporia or impasse: death, disaster, catastrophe not as “accident” but “necessity.” “Set-up” is a synonym for “apparatus.”

The risk Heidegger takes in generating this reading of the fragment enables a leap out of literacy into electracy, for in searching for le mot juste for the truth of Being he names exactly the problematic of the coming apparatus, and here is the entire point, message, passage, imperative. His strategy is to rethink the sense of category as “indictment” (the handing down—or up—of accusation, the metaphysics allegorized in Trials from Socrates to Kafka), to hear this handing over and exchange as the coming into presence of Being as a certain enjoining, and finally, enjoyment. “Necessity” becomes “Usage” (der Brauch). “Justice” in this reading enjoins each epoch to bring about what is fitting, appropriate, in the manner in which what is given belongs together.

“Usage” should not be understood in these current derived senses. We should rather keep to the root-meaning: to use is to brook [bruchen], in Latin frui, in German fruchten, Frucht. We translate this freely as “to enjoy,” which originally means to be pleased with something and so to have it in use. Only in its derived senses does “enjoy” mean simply to consume or gobble up. . . . “To use” accordingly suggests: to let something present come to presence as such; frui, to brook, to use, usage, means to hand something over to its own essence and to keep it in hand, preserving it as something present. . . . “To brook,” frui, is no longer merely predicated of enjoyment as a form of human behavior; nor is it said in relation to any being whatsoever, even the highest (fruitio Dei as the beatitudo hominis); rather, usage now designates the manner in which Being itself presences as the relation to what is present, approaching and becoming involved with what is present as present. (Heidegger, Early Greek Thinking)

Why go into this detail (apologies)? Here is the lesson of heuretics that may guide inquiry into and creation of the coming education: Enjoyment is to electracy what Truth is to literacy, shifting ontology from substance to relations, from cogito to desidero. There are as many versions of “relation” as there are ontologists today, but they share a consensus. Heidegger’s inventive translation developed the rich semantic field of this name. The manner of accomplishing enjoyment, however, turns out to be as troubled as were the primary purposes of the previous apparati. We won’t follow this path any further here, other than to note that it passes through Jacques Lacan’s jouissance (blissense), including his myth of the “lamella,” the organ without body representing the libido or life force itself. The importance of this mythical organ for apparatus theory is in the question of the sensorium in electracy. Each apparatus reconfigures the sensorium relative to the human-technology interface, as in Walter Ong’s explanation that in orality hearing organizes the sensorium, while in literacy it is vision.

Working over “Enjoyment” in his turn, Lacan invokes Heidegger’s translation of Anaximander, to confirm “usufruct” as the proper focus of electrate metaphysics, with lamella as the ordinating organ. The issue of “modality” arises in this context, to challenge the rather sanguine attitude that our disciplines seems to have toward “multi-modality.” The neutral listing of modes—”textual, aural, linguistic, spatial, visual” for example—neglects the apparatus sensorium that requires consideration of the organs relative to the erogenous zones. The lamella gathers together as mythical organ the part-objects (breast, feces, phallus, sight, voice) as articulations of the new “thing” of electrate metaphysics, what Lacan calls the objet petit a (object little other, the @ as it is sometimes written), the object cause of desire. This metaphysical entity allows access in thought, perception, language, and action to the energy of the libido, structured by attraction-repulsion. It is to this metaphysics Helms refers when characterizing Rhizcomics as energeic, alluding to Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy. In Seminar X, Anxiety, Lacan shifts attention from the phallus (imaginary or symbolic) to the organ proper of the penis, in order to introduce the whole question of the objet @ in its several “decidual” or separable organs, to clarify what is involved in the so-called castration complex. Here is a metaphysical sound barrier, when the wings fall off the test vehicle.

The entire system of attraction-repulsion finds its emblem in this im/potence of the male sexual organ, its coming and going, its in/capacity fundamental to the enjoyment of both sexes, with anxiety as a signal of the real that does not deceive. Anxiety, whether Heidegger’s or Lacan’s: such is the modality that must be submitted to apparatus invention—not the neutral description of true-false, but the modality of privation, “not/to-be-able,” or even “I-would-prefer-not-to,” experienced not as reason in understanding, but as anxiety in desiring. Usufruct regarding “availability” of organs includes repulsion in the claims on other bodies articulated by the Marquis de Sade, as Lacan explained regarding the similarity between Sade and Kant. The rhythm of coming and going noted by Heidegger is emblematized in the de/tumescence of the male organ, and developed in its full metaphysical significance in the oscillating systole-diastole discussed by Deleuze in the Logic of Sensation, on the paintings of Francis Bacon. Here is the challenge for anyone too complacent about our digital paradigm shift. The Academy today remains the institution of literacy, in the modality of true-false. Are we even capable of heuretics supporting a sensorium of lamella? And yet that dimension of appetite is precisely our calling and always has been. To predict the future of electracy based on the template of literacy, then, is to begin to imagine what might be the nuclear physics of libido.

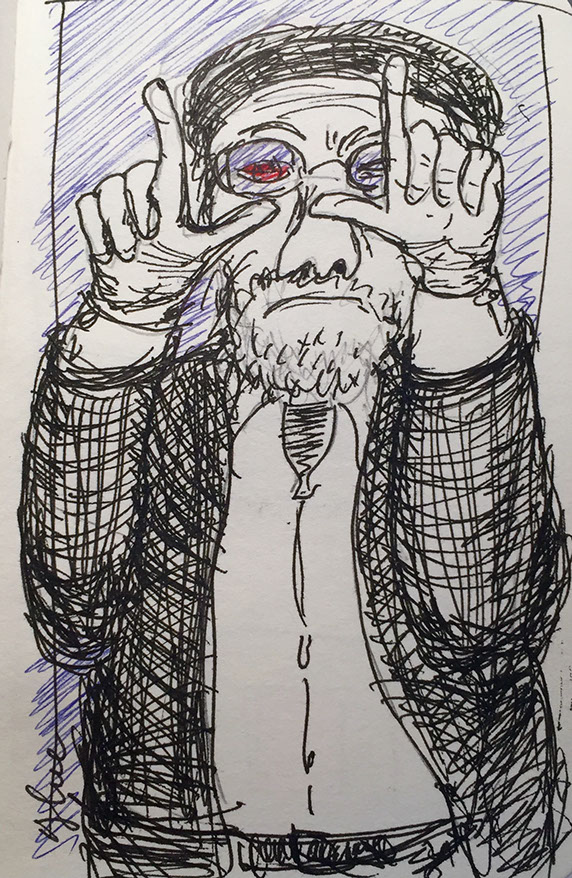

Where does comics figure in this framing? Rome was not built in a day, literacy did not happen all at once everywhere, nor is it one (as Derrida insisted from the beginning, with caveats not to remain confined to the history of alphabetic writing only). There is just space enough to acknowledge the post-critical dimension of Rhizcomics to which I am most indebted. Helms references Ulmer’s post-criticism (text-shop) as an immediate influence—a practice of applying all the devices of modernist arts invention as modes of inquiry and learning. Thus Rhizcomics is not only about comics as rhetoric, but itself performs a comics “modality” including text-image relations, nonlinear narrative and associative figurality, and most importantly—drawing. What most impressed me about Helms when we met, beyond his familiarity with electracy and Classical Greek, and that truly marked a leap beyond Ulmer (and even Derrida), was that in order to pursue the questions encountered in his research he had learned how to draw. Oh this simple statement hit me as a revelation. Perhaps I masked the effect by pretending to choke on my croissant, or spewing coffee out my nose. Part of the recognition was owing to the translation it provided of a rebus in my image of wide scope, composed years ago as a test for the mystorical pedagogy used in my Hypermedia seminars. My wide image—the emblem representing the pattern formatting my imagination—is a pentagram, embodied as logo in a sheriff’s star, specifically the star that Gary Cooper as Will Kane takes off and on several times during the drama of High Noon, the showdown with the gang of killers. Kane was not able to raise a posse (Latin possum, I can), and he feels obliged by his manhood to confront the killers in a gunfight. We have the topos of the Western showdown: draw! The joke itself was nothing new (the pun on “draw”). What was new was the recognition that I was the addressee of this imperative: Ulmer, you draw! And thereafter I began my own apprenticeship, undertaking an assignment I recommend to you as well, borrowed from Paul Klee’s illustration of Voltaire’s Candide: experiment with the transition from literacy to electracy by illustrating a text of your choice. In my case, that text is Heidegger’s essay on Anaximander: to draw Fug.

At the time I was like the sage who swore that he would not venture into the water until he had learned how to swim, in that the first lesson I took from Helms was to shift the focus of my heuretic template to drawing in search of an electrate equivalent for the law of the excluded middle that structures Aristotle’s invention of logic. This research sent me back to Sergei Eisenstein, featured in Applied Grammatology for his unfinished project to apply intellectual montage to a film adaptation of Marx’s Das Kapital. In this new context the focus was on his vision of the plasmatic line, reified in the early animations of Walt Disney and his mouse, Mickey. The plasmatic moving line is the fundamental operator of electracy.

This is also Disney’s amazing elastic game of the outlines of his creations. When amazed, their necks grow longer. When running in a panic, their legs get stretched out. When frightened, not only does the character shake, but a shuddering line runs along the entire outline of his shape. Here, namely in this aspect of the drawing, the very thing that we have just presented so many examples and excerpts from comes into being. . . . And only from the moment when the line of the neck elongates beyond the limits of possibility for necks to elongate does it begin to be a comical incarnation of that which takes place as a sensuous process in the previously discussed metaphors. The comical here occurs because every representation exists dually: as a collection of lines and as an image which grows out of them. (Eisenstein, “Disney”)

Eisenstein’s plastmatics opens onto the entire history of the line of depiction, prompting us to extend our history back to the Paleo apparatus, already studied by one of Derrida’s sources, André Leroi-Gourhan. The line of depiction is part of apparatus invention, fundamental for the Paleolithic epoch. One account explains that the sudden appearance of cave art forty thousand years ago, and its rapid dissemination, is due to the same conditions of discovery manifested in other apparatus inventions such as the alphabet or the printing press. The curving inflected line of depiction extends from Chauvet cave (see Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams) to the continuous variation of parametricism in contemporary urban design, as in Zaha Hadid’s Masterplan for Istanbul. The animated line (producing the effect of “life”—the vectoral arrow) is accounted for within the philosophy and mathematics of the fold. This path passes through Deleuze and Guattari, to be sure (Deleuze’s The Fold on Leibniz and the Baroque), and draws upon topological or “rubber-sheet” geometries in general, referenced in the plasmatic transformations of cartoons, not to mention Jacques Lacan’s Borromean knots.

One of the most important theorists of the dynamic line is René Thom, whose catastrophe theory is widely cited. Thom’s seven elementary catastrophes chart the movement of change in any process, as in the cusp catastrophe, which is the one whose diagram tends to serve as the emblem for the study of dynamical systems. Thom’s geometries record in fact the dynamics of desire, of attraction-repulsion across all dimensions, with the prototype being the cycle of predation, the interaction between predator and prey.

In human as in animal action, there is as it were a “thickening” of abrupt (catastrophic) transition between the virtual investment of a subject by a pregnance and the “satisfaction” resulting from the act. There can scarcely be any doubt that the essential function of that part of speech we call “verb” is to symbolize this transition. Thus the typical transitive sentence (the cat eats the mouse) describes a process that can be formalized as follows: 1) The subject is assailed by a virtual pregnance (desire with no immediate object). 2) The object appears. The subject then emits in its direction a “local” pregnance which reaches and invests the object (unless there is failure!). 3) Following this investment there is conflict in the state of the object between its own individuating pregnance and that received from the subject. 4) The result of the conflict—seen as a transformation of the state of the object—is implicit in the meaning of the verb expressing, in particular, the subject’s “satisfaction.” (René Thom, Semio Physics: A Sketch, my emphasis)

The figure of fold dynamics is the cat eats the mouse. The heuretic CATTt. We are in a bachelor machine. In explaining his geometry Thom refers to the example of the cat chasing and eating the mouse, while admitting that the hunt does not always succeed. This prototype is central to the invention of eletracy, by identifying the metaphysical import of the animated cartoon as recounted in a study such as Norman M. Klein’s Seven Minutes: The Life and Death of the American Animated Cartoon. In this context we recognize that the cat and mouse chase central to cartoons constitute for electracy the equivalent of the allegory of the cave, recorded in Plato’s Republic. The cartoon chase dramatizes in seven minutes the metaphysics of electracy. Klein recommends a pre-Disney Felix the Cat exemplar to represent the mode, “Felix Dines and Pines” (available on YouTube), which covers the entire predation cycle, including its failure and compromises, and the surrealist dreaming that follows satisfaction (diurnal-nocturnal rhythm). The strategies constituting the gag logic of the cartoons demonstrate that as a metaphysical allegory of desire, of attraction and repulsion, the purpose is to keep the game going: play (not consumption). Lacan says as much in his description of drive, separated from literal need at the level of biology, since desire as such may never be satisfied. The circling of drive around the object cause of desire (objet @), whose real enjoyment is the repetition of the cycle and not completion of a goal, is perfectly represented in the allegory of the chase cartoon, with Hanna and Barbera’s Tom and Jerry refining the genre to “pure chase” (or Chuck Jones’ Coyote and Roadrunner). Now we know why seemingly every other live-action film includes a chase sequence, celebrating our predator parallax vision. If we were Houyhnhyms, it would be otherwise.

It is possible at this point to assert the framing analogy guiding the heuretics of electracy, in the transition from Ulmer to Helms: Disney is our Plato, Disney World our Academy, Entertainment rather than Science, corporation rather than state, Mickey Mouse our Socrates, the cartoon our dialogue, the gag our argument, augmenting fantasy not logic, supporting desire not reason. Literacy continues meanwhile, and does not require further invention. Is this catastrophe present in your curriculum? A new dimension is opened in Electracy, neither the space of spiritual faith in Heaven, nor the natural material order of science, but the dimension of fantasy that Lacan insists accompanies and enables desire. Sixty-six million tourists visited Orlando, Florida, in 2015 (thank you), but the attraction is not confined to built establishments, the theme-parking of global society, as they say, with prototypes being not only Disney but Las Vegas, The Mall of the Americas, and even Manhattan itself, generated out of Coney Island, as Rem Koolhass argued in Delirious New York (known as “soft-targets” in Jihadi). Americans enjoy over eight hours each day of screen time engaging with this electrate dimension. Disneyization is much lamented among educators who fail to recognize the catastrophe as metaphysical. From the point of view of literacy, electracy looks like The Matrix. The book Jihad Versus McWorld: Terrorism’s Challenge to Democracy, by Benjamin Barber, is a useful account of some of the global issues, clarifying that the “clash of civilizations” is rather a clash of apparati: oral (religion), literate (science), and electrate (entertainment corporation). Kim Jong-un perhaps gets it better than most.

The implications for the coming education are profound, extreme, and troubling. We may prefer true-false to attraction-repulsion, but our best thinkers warn us that the industrialization of fantasy threatens to kill desire. We won’t need to worry about fossil fuels if we run out of libido. The metaphysics engages not life, but life-death, and now has accessed the energy of libido itself. You may have noticed our politics becoming increasingly impervious to reason, evidence, facts, or even reality-testing. Now we know how believers felt when Galileo attempted to show them a different dimension. We accept that Heaven is a fantasy. Is Nature also? We understand that identity in electracy is other than selfhood and democracy, and is undergoing reformation. If that task seems im/possible, we may be reminded that the distance from one elm to the other is not so great. The operating practices of electracy already exist, created in the modernist revolutions across all media, modes, and disciplines (post-criticism). The disciplines of rhetoric know it well: gags work like dreams, and dreams are tropology functioning as psychic defense. If the Unconscious were a homunculus, it would be a Renaissance Neo-Platonist, Lacan once joked, although no doubt it would appear as Kafka’s Odradek. René Thom’s Semio Physics is a turn on Aristotle’s privative mode. The fundamental challenge for academics is to accept responsibility for attraction-repulsion, working over critique with fantasy, so as not to give up on desire (Lacan). There is no better site for this shift than comics, as I learned from Helms.

Perhaps an entry into the larger question might be a screening and discussion of the documentary “Life, Animated,” directed by Roger Ross Williams, about an autistic child who eventually was able to reconnect with his family and reality through obsessively watching Disney films. I cannot tell you how many mystories of my students over recent decades, for better or worse, cited a Disney movie in their Entertainment slot of the Popcycle. Rhizcomics is an event within this larger project of invention, a straw in the wind. We academics are the successors, the diadochi, of the original Academy, and our role is not simply to follow in the footsteps of Aristotle, but to seek in our own digital civilization what he sought for alphabetic writing. The challenges are obvious, and no doubt my account of the apparatus itself is open to debate. My granddaughters are returning from Orlando at this very moment, sated perhaps, already dreaming. Consider what is at stake in our world today, registered in the basic fact that the anthropocene coincides with electracy. We notice immediately that prayer and engineering do not suffice, and no one doubts they are trying. We desire effective change but are not able, we cannot despite our will and knowledge. Here is the modality specific to electrate metaphysics: to be able. Invention required. Draw.

Gregory L. Ulmer

University of Florida

Gainesville FL