A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: Understanding Expectations and Mapping Preferences for Writing Classroom Design

Dana Gierdowski and Susan Miller-Cochran

Discussion: Identifying Emerging Themes

In our analysis of the results from the expectations survey and the student conceptual maps, we identified several emerging themes. Although the participant sample for phase 3 of the study is small (N=24) , the emerging themes were prominent across the sample. Of note were themes that clustered around the following trends: technology (not) included on student conceptual maps, an emphasis on mobility, the positioning of the instructor, and a focus on comfort.

Technology (Not) Included on Student Conceptual Maps

One of the trends that stood out to us in our analysis was the pattern of technology that students chose to include—and sometimes not to include—on their maps. Specifically, we noticed that several students did not include specific notations about technology included in the classroom. Six students did not include student technology in the room, and ten students did not include instructor technology. An additional three students only included instructor technology that might seem outside the norm: gaming consoles and surround-sound speakers.

We also noticed that twelve students—half of the participants—did not include writable surfaces in the classroom. One explanation for this trend is that students might be assuming what is, by default, included in a classroom. In the classroom building where this study took place (and where most students had class), all of the classrooms are smart classrooms with instructor desktop computers, projection capabilities, and document cameras. They all have whiteboards in the front (and in some rooms, the back) of the classroom as well. If students assume that such technology is included in all classrooms, then they might not think to include it on a map of their ideal classroom, instead choosing to focus on the elements that aren’t typically in a writing classroom that they want to highlight. This might also explain the frequency with which students referenced tactile interfaces and touch screen technology such as tablet computers, Smart Boards, iPads, and surface tables. These technologies, at least at the institution in this study, fall outside the norm for classroom technology provided in writing classes, so it would make sense that students would take time to include elements that would be unusual.

When students included technology for themselves on their conceptual maps, they tended to include student-provided technology instead of institution-provided technology. When these results are interpreted in conjunction with the expectations survey, the frequency with which students expected to use their own computers helps explain the absence of provided technology on the maps. On the expectations survey (N=371), 73 percent of respondents “always” or “regularly” expected to use their own technology in the classroom. Perhaps what we can learn from these results is that students prefer to provide their own technology in the classroom, and they are also open to using mobile technologies outside of the typical laptop and desktop computers found in a typical computer classroom design.

Student expectations to use their own writing technology in class have several implications for the design of learning spaces for writing instruction and represent a departure from common writing classroom designs and assumptions about institutional provision of instructional technology. If students bring their technology to class, then instructors can teach them to work in their natural writing environments. The instructor’s role, then, shifts to one of helping students customize their writing environments and learn to work efficiently and effectively with the tools at their disposal. The walls of the classroom become less of a barrier, allowing students to take their work—and the technology that feels familiar and comfortable to them—inside and outside of the classroom. If one of the goals of first-year writing is to help students develop tools they will take to writing tasks outside of the immediate classroom environment, then it makes sense that students would practice using those tools in the digital environment in which they would write outside of the classroom walls. Designing learning spaces where students are invited to use their own technology in the classroom also renders debates about banning student technology in (at least some) learning spaces irrelevant.

Emphasis on Mobility

Over half of the student maps indicated that some or all of the student furnishings would be mobile. Movement in the classroom space seems appealing to students, and it was most evident in the designs that incorporated learning/writing “stations” throughout the room. Student participants (N=24) in the conceptual mapping portion of the study came from all four of the different classroom environments in our program; only four were in the flexible classroom. Even though most of the student participants had not been in a flexible classroom for their writing class, they recognized the potential advantages of being able to easily rearrange furnishings to facilitate group work and active learning.

Because students tended to design spaces that could facilitate a variety of pedagogical configurations—including small-group work and active learning—it seems logical that their learning space designs would follow less of a teacher-centered, transmission model. Surprisingly, though, students still gravitated to this more traditional perception of the position of the instructor in the classroom.

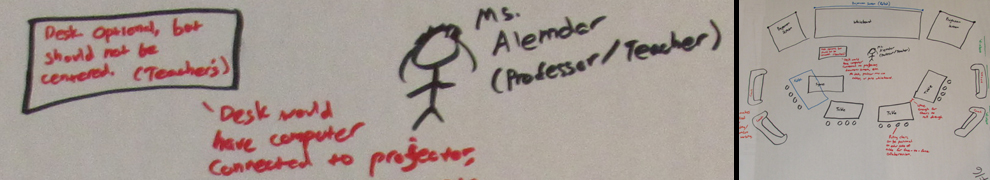

Position of Instructor

Although the majority of students made student furnishings in the classroom mobile, they still tended to position the instructor at the front or center of the classroom, maintaining a teacher-centered space. On these maps, the instructor remains in a central position of authority in the room. The results from the expectations survey shed light on a possible explanation for this trend, however. Students participating in the expectations survey (N=371) at the beginning of the semester came to their first-year writing classes with a high expectation that they would experience a transmission model of education: 86 percent of the respondents indicated that they “always” or “regularly” expected to hear lectures in a writing class.

Although the student conceptual maps indicate that some students had shifted their perspective to include an element of group work in the classroom by the end of the semester, the positioning of the instructor in the classroom indicates that they still hold onto the notion of the teacher as the authority figure and knowledge provider in the classroom. These results seem to conflict with the tendency to design the room with the ability to move into group configurations, ostensibly to facilitate engaged group work. Hunley and Schaller (2009) provide some direction on how to interpret these findings and draw conclusions from them. They wrote that students in their study reported feeling less responsibility to participate in a traditional classroom (with the instructor positioned at the front); as a result, they concluded that student engagement is more profound when students are situated in a learning space where they “hold ownership” (34). Therefore, we argue that even though students seem to place the instructor in the position of authority in their mobile classrooms, decentering the space and giving students more ownership of the space in the room could increase student engagement.

An expectation of hearing primarily lectures could also contribute to a sense of rootedness in a particular space in the classroom, contradicting the mobility provided for on the student conceptual maps. Such rootedness could impede students in participating in the group writ large and hinder the benefits they might gain from exchanging ideas and co-constructing knowledge with their peers. In researching learning spaces, Boys (2011) suggested that

we need to explore how different learning spaces can make participants (tutors as well as learners) feel safe or uncomfortable, and the impact this can have on their learning. If a space is very "recognisable," for example, a lecture theatre, then is it likely that students will fall into standard assumptions about their "place" as a passive rather than an active learner, and may in fact prefer such a location, since it represents what they already know. On the other hand, the strangeness of having "standard" routines shifted, without clear alternative rules being offered, may undermine confidence. (46)Some of the student conceptual maps included elements that seem to fall into these standard assumptions. The competing nature of the mobile student furnishings in a teacher-centered space indicate that, after a semester of first-year writing, students seem willing to accept an active learning model with a participatory focus, but they are still more comfortable with the idea of a teacher-centered classroom. Such a result points to the need to orient students to an active learning model instead of assuming that students will already be prepared to participate in active learning or will adjust on their own. That is, we must teach students how to interact and collaborate in a class where such participation will be expected and an integral part of learning.

Focus on Comfort

A final trend that we noticed in our analysis was a distinct emphasis on comfort in the classroom setting and an attention to aesthetics. A prominent theme was that students seek comfort in their seating, including elements such as soft seating, couches, and bean bag chairs. They also seek comfort in the lighting in the room, with several students indicating the need for “natural light.” Students are drawn into a space that might feel unfamiliar to them in a writing class, and their designs show ways that they are reintroducing an element of comfort into a learning space.