A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: Understanding Expectations and Mapping Preferences for Writing Classroom Design

Dana Gierdowski and Susan Miller-Cochran

Review of Literature

Complicating Spaces

Similar to the early discussions taking place in our writing program, scholarly discussions of instructional environments for writing tend to focus first on the modalities of instruction and the approaches that are most pedagogically effective in a variety of mediated learning environments. In discussions of these learning environments, the actual places in which we teach and learn are often neglected as a focus. Composition scholar Nedra Reynolds (2004) reminded us in Geographies of Writing: Inhabiting Places and Encountering Difference that we should not ignore the physicality and materiality of learning environments, asserting that “places are hugely important to learning processes and to acts of writing because the kinds of spaces we occupy determine, to some extent, the kinds of work we can do or the types of artifacts we can create” (157). In “Hacking Spaces: Place as Interface,” Doug Walls, Scott Schopieray, and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss (2009) wrote that scholars in computers and writing have focused on issues of space related to software, access, virtual space, and physical design. However, they argued that “physical space is perhaps one of the most important, yet often overlooked, issues of interface that we negotiate as writers, researchers, and teachers” (p. 273). The design of learning spaces “often takes a back seat to budgetary concerns, institutional politics, and physical constraints” (Carpenter et al. 2013, 316).

The scholarly conversations in rhetoric and composition regarding place and learning spaces have largely been discussed in broad terms, such as the impact of the spatial metaphors used in composition spaces, as well as the pedagogical approaches useful in a variety of learning environments. Scholars in the field have suggested approaches that encourage us to be more mindful of place, including a re-conceptualization of spatial metaphors to better understand student writers (Reynolds 1998, 2004), as well as pedagogical practices that afford students greater freedom to explore their identities through the influence of place on their lives (Ball 2004; Benson 2010; Burns 2009; Gruenewald 2003; Lauer 2009; Mauk 2006; Shepley 2009). Inspired by the point made by Anne Frances Wysocki and Julia Jasken (2004) that “the design of software is thus also the design of users” (35), Walls et al. (2009) asserted that “the design of spaces is thus also the design of users—and, importantly, also the design of the uses of particular spaces” (273).

We extend this argument by asserting that writers are also actively designing learning and composing spaces through their uses and perceptions of that space. In Natural Discourse, Christian Weisser and Sidney Dobrin (2001) pointed directly to the theoretical importance of place in composition studies and argued, “Discourse does not begin in the self, as some expressivist theories and pedagogies have erroneously suggested; rather, writing begins externally in location. Writers write by situating themselves, by locating themselves in a particular space/context” (8). Reynolds (1998) pointed out that the territorial metaphors (such as frontier, city, and cyberspace) historically associated with rhetoric and composition are imagined and, as a result, mask the politics of space and place, such as institutional power, gender, race, and cultural inequalities. In other words, such metaphors can be a challenge for students to relate to given the diverse backgrounds from which they come. The consequence, then, is the neglect of “material spaces and actual practices” (Reynolds 1998, 14). Tangible space is very much tied to the discursive spaces of instruction, and these areas deserve critical attention. Therefore, we have designed our study to invite students into a conversation about learning space design, to share their perceptions of learning spaces, and to show us the ways they would prefer to situate themselves in learning spaces.

Exploring Learning Space Design

To develop a design for a systematic study of student expectations for and perceptions of our new flexible learning space, we looked to some of the foundational scholarship on learning space design. Learning spaces have been studied from a variety of perspectives in recent years; however, the bulk of the empirical research in this area has come from the field of science education. The work of Robert Beichner and his colleagues (Beichner et al. 1999; Beichner et al. 2007) is of particular note, as their development and research of the SCALE-UP (Student-Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) Learning Initiative in physics education spans nearly two decades and has been implemented and adapted at institutions worldwide. Active learning is encouraged through hands-on pedagogy, as well as through the physical design of the classroom, which includes round tables, LCD monitors and white boards on the walls, and no formal classroom “front.” They wrote, “An effective studio class will take place in a room where the instructors can easily move around to interact with each group, identifying and helping students with difficulties, as well as ensuring that no student can avoid interacting with instructors by hiding in the middle of the row, away from the lecture hall aisles” (Beichner et al. 2007, 3–4). Results from studies in SCALE-UP learning environments have shown an increase in conceptual understanding; improved attitudes; higher class attendance; and reduced failure rates for women, minorities, and other “at risk” student populations.

We also looked to studies that have examined student expectations about classroom design as guides. Gaffney, Housley-Gaffney, and Beichner (2010) examined student expectations when working with SCALE-UP pedagogy by surveying physics students at three universities regarding their expectations about having class in a SCALE-UP room, which the researchers posited could be a “jarring reality for a college student entering a classroom that is not only physically different, but also promotes participation in ways that are unfamiliar or uncomfortable.” The results of student surveys revealed that students initially expected a lecture-style class that would not require them to share their work or communicate regularly with their peers. Gaffney et al. noted that prior classroom experiences inform student expectations, which have the potential to affect their “satisfaction, motivation, and perhaps even their ability to learn.” Sawyer Hunley and Molly Schaller (2009) also found that students’ perception of the classroom space was influenced by their previous experiences. Ultimately, Gaffney et al. (2010) claimed that “investigating the complex relationship between student expectations and their perceived experiences in reformed physics classes is an important step toward understanding what makes for successful implementations of pedagogical reforms that have demonstrated the potential to produce strong learning gains.” We add that parsing student expectations about and perceptions of what they will experience pedagogically in class from their expectations about and perceptions of the learning space design itself can be challenging. For this reason, we turned our attention to two types of data collection: data to help us understand student expectations about what they would experience in a first-year writing class and data about their perceptions of the design of the learning spaces in which they took those writing classes.

Building upon the work of other learning space scholars, as well as those within the field of rhetoric and composition who have studied space and its relationship to writing and writing pedagogy, we designed a study that would allow us to systematically investigate student expectations about a writing class and their preferences for writing classroom design. In this study, we respond to three research questions:

- What do students expect they will experience in their first-year writing class?

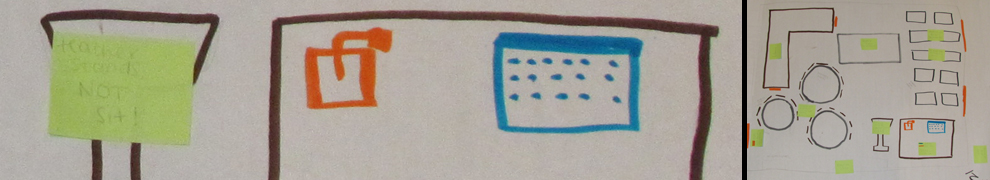

- How would students design an “ideal writing classroom,” given no budgetary or administrative constraints?

- What expectations about writing classrooms are evident in those designs?