Review by Lilian Mina

Read more about session K1 on the C&W conference site.

View video of Kyle Stedman, Tekla Hawkins, and the session Q&A online.

View Bill Wolff’s video online.

Panelists

Tekla Hawkins, PhD candidate at University of Texas at Austin

Bill Wolff, Associate Professor at Rowan University

Kyle D. Stedman, Assistant Professor at Rockford College

Tekla Hawkins, “Mixtape Fairytales: Fan Fiction and Digital Literacy”

Hawkins introduced fan fiction as gateway writing, but there are concerns about it being immature or academic writing. She asked an important question about the usefulness of fan fiction for Rhetoric and Composition. She sees fan fiction as the genre that remixes other types and genres of writing.

Hawkins said that fan fiction is so popular that we can’t just ignore it, and that it must be doing something good if millions of people read it. Hawkins contested the common belief that fan fiction is not “good” because it is perceived by many as “derivative” rather than “transformative,” and that the Rhet/Comp people still think negatively of derivative works. This perception, she argued, reflects how our field still thinks of original writing. Therefore, Hawkins proposed that we read fan fiction as new media objects rather than genre fiction to make it fit in our field. She explained her proposal by arguing that fan fiction does what digital remix does all the time, so it can’t be derivative even though it’s less transformative.

Hawkins also pointed out that fan fiction acts like an interface that gets us into the canon of knowledge of databases (e.g. a database of Harry Potter novels and movies) in a new way.

The interesting part was when Hawkins argued that fan fiction allows people to (re)imagine all types of stories, which is inherently rhetorical. This argument made me think of the significance of fan fiction for our society as well as our classes. For the society, it means people tacitly learn about rhetoric by reading the genres they like. For the writing class, Hawkins’ argument presents a fun and lively way to introduce rhetoric to students framed in the fun genre of fan fiction instead of the traditional lifeless methods or approaches.

Bill Wolff: “Baby, We were Born to Tweet: #Springsteen, Concert Tweets, and the Emergence of a Transmedia Composing Community”

Wolff opened his presentation with a clip from a Springsteen concert before he moved to discussing his study and how to bring Twitter-based studies to the classroom.

He talked about the different methods of archiving Tweets, such as j.mp/yourtwapperkeeper, and the need for a researcher to filter through the tweet archive so that they wouldn’t get lost in the huge amount of data available there.

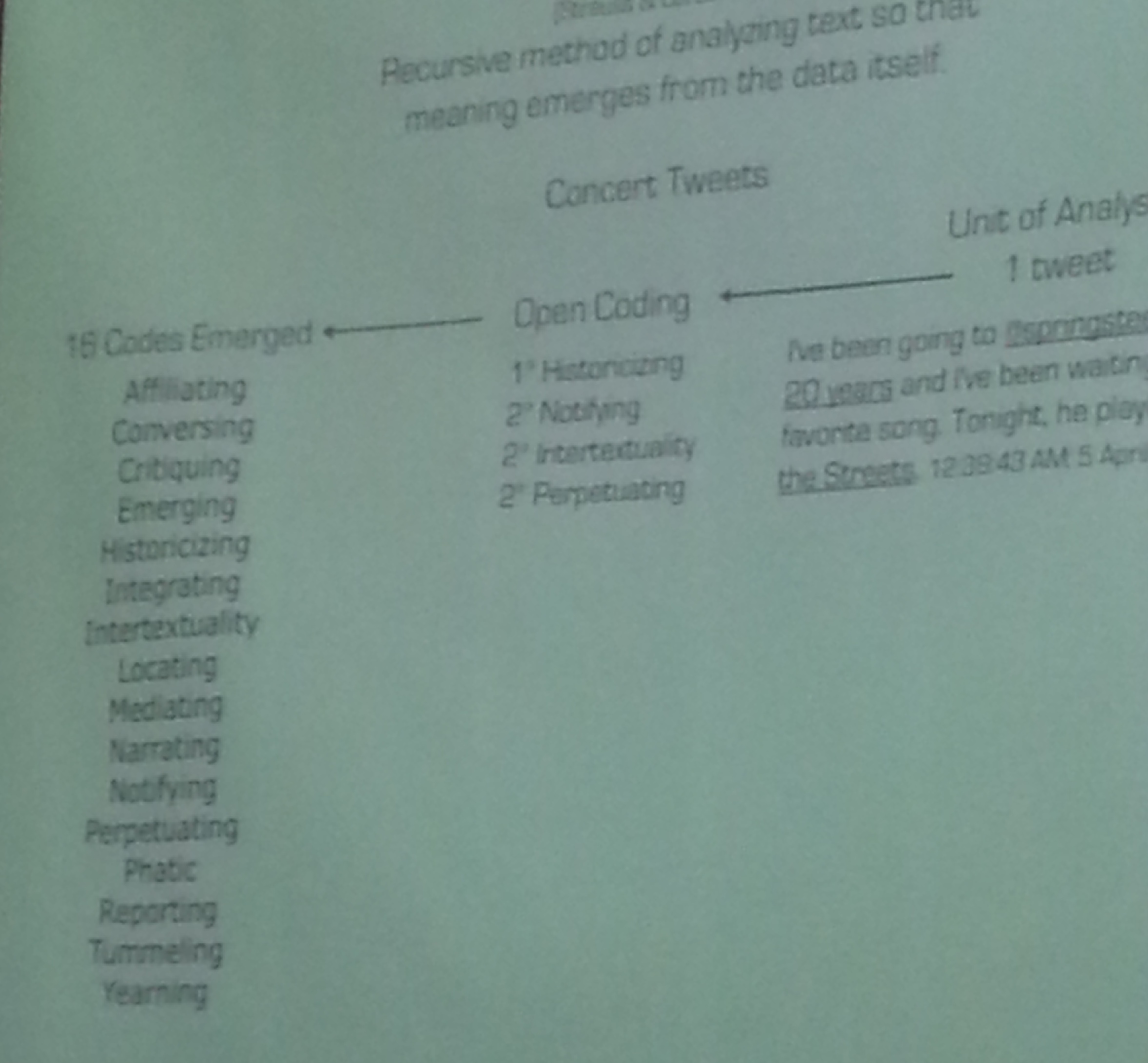

Wolff then explained the details of the study on a corpus of tweets about one Springsteen concert. This was the fun part for me as a researcher. Wolff explained how he chose to use Grounded Theory for coding the data but he realized later that what he was doing was not really Grounded Theory.

He shared his coding system with the audience of the panel. He broke down his codes into primary and secondary codes. The primary codes included historicizing, notifying, intertextuality, and perpetuating, while the secondary codes included conversing and reporting as you can see in the picture. Afterwards, he shared a table of his findings resulting from a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods.

During the Q&A session, a member in the audience encouraged Wolff to report the details of his methodology in any publications based on this study because our publications lack depictions of methodologies. As an advocate of mixed-method design studies, I found his quantitative and qualitative analysis of the tweets corpus so fascinating that I asked him and the audience whether research on social media is bringing qualitative methods to Composition studies again. The reason I asked that question is that Wolff’s presentation was the fourth to utilize mixed-method design at C&W. I really hope Wolff discusses his methodology in his coming publication of this study.

Wolff pointed out that understanding the context of tweets is highly significant to unlock the real meaning of the tweets. He believes that we should study tweets as contextualized, artifactual objects. In other words, we should pay attention to the spaces, texts, genres, and artifacts of tweets.

Kyle Stedman, “Toward a (Fannish) Phenomenology of Sound: Nostalgia, Affect, and Lightsabers”

In a presentation about fandom, sound, and phenomenology, Stedman discusses three perspectives researchers have taken in dealing with the phenomenology of sound.

The Philosophical perspective deals with how we feel as we listen to certain sounds. Stedman presented Don Ihde’s contention that the philosophical phenomenology of sound means listening to the sounds and our feelings about them. He explained how he felt when he listened to the track “Remembering Jenny” from “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” because of the memories that track brought back to him.

Stedman gave another interesting example of how the Prelude track used in Final Fantasy series of videogames resembles Camille Saint-Saens’ Piano Trio No. 1 in F Major. This means that sound becomes a phenomenon that is linked to particular feelings it stirs every time one listens to that sound.

Stedman’s examples made me realize that every time I listen to Abba’s song Chiquitita, I still get the same feeling of peacefulness filling me, and as the song comes to its musical end, I feel as excited and cheerful as I felt the first time I listened to it two decades ago. Obviously, this is called philosophical perspective of the phenomenology of sound. Nice!

The Scientific approach to the phenomenology of sound means our ability to recognize objects from the way they sound. Stedman presented Vicario’s proposition that we catalog sounds “based on their perceptual characteristics, and not on physical or physiological prejudices” (Vicario 21). He gave the exciting example of laser and how it became associated with a certain sound in our heads because of the numerous times we watched media representing laser to have a certain sound despite the fact that laser has no sound. On the contrary, the 80 pianos playing Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue at the Los Angeles Olympics sounded the same as a soloist pianist even though they looked different.

The Ontological approach to the phenomenology of sound means that two things are considered side-by-side: the sonic phenomenology (how sound seems to listeners) and the sonic ontology (how the sound really is). Stedman used Stuart Jones’ research on melody to support the argument that we link notes together even though they are not linked in reality. He also used the example of how the TARDIS sound was used to celebrate British pop culture at the opening of London 2012 Olympics.

Stedman’s presentation gave the audience a brief summary of the different approaches to sound as a phenomenon, which could be used in composition classes studying sound or composing audio texts. To me, it means more reflection on what I think and how I feel every time I play some of my favorite music. I personally like the philosophical perspective and am starting to think of how to bring it to my writing class. After they compose their multimodal projects, I may ask students to reflect on the music and sounds they used and how each track made them feel or how it relates to the project as a whole. Worth trying!

Lilian Mina is a Ph.D. Candidate at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.