The idea for this assignment, taught in a junior-level composition/gender studies course at Ohio University, came to us while Gamergate was at its nadir. The loosely organized social media campaign attacked game developer Zoe Quinn and her Twine based game, Depression Quest, for its fundraising via the platform Patreon and because they felt–although this was proven to be false–that Quinn had received undo praise for the game because of her romantic involvement with a games journalist. At the heart of this attack was a construction of “gamer” as an essentialized identity; one that is male, socially conservative, and anti-feminist. The campaign grew to include other female game developers, their supporters, and games journalists and computer and gaming companies. It included doxxing (the publishing of a target’s personal information–often including home address, phone number, and workplace–online), harassment, and threats that drove Quinn and her family from their home.

It was clear to us that if we wanted to explore women writing in digital spaces with our students, we needed to engage with the resistance that women often encounter when they speak or create online. Although Gamergate was the most visible example at the time we were planning this course, it was by no means unique. Women writing online face significantly more–and different kinds of–harassment than men writing online, and the emergence of this new sort of gendered violence is unfortunately key to understanding why women do, and do not, participate in digital discourses.

We were further motivated by the need for critical analysis and interrogation of the violent treatment, erasure, and overall misogynistic representation of women in mainstream video games. Students working on this assignment were challenged to create a narrative game which could appropriate and disrupt the genre to represent women and lgbtq identities in more complex and nuanced ways, and to give these identities more agency by creating their own digital narrative games that examined a social issue centered on gender or sexuality. In the sections below, we link to a student-created Twine game example, “A Journey Through Gender,” describe and provide the assignment, and finally, discuss how the genre of the narrative game or “gamebook” becomes a productive way to approach teaching gender politics and writing.

Student-Created Twine Game: “A Journey Through Gender”

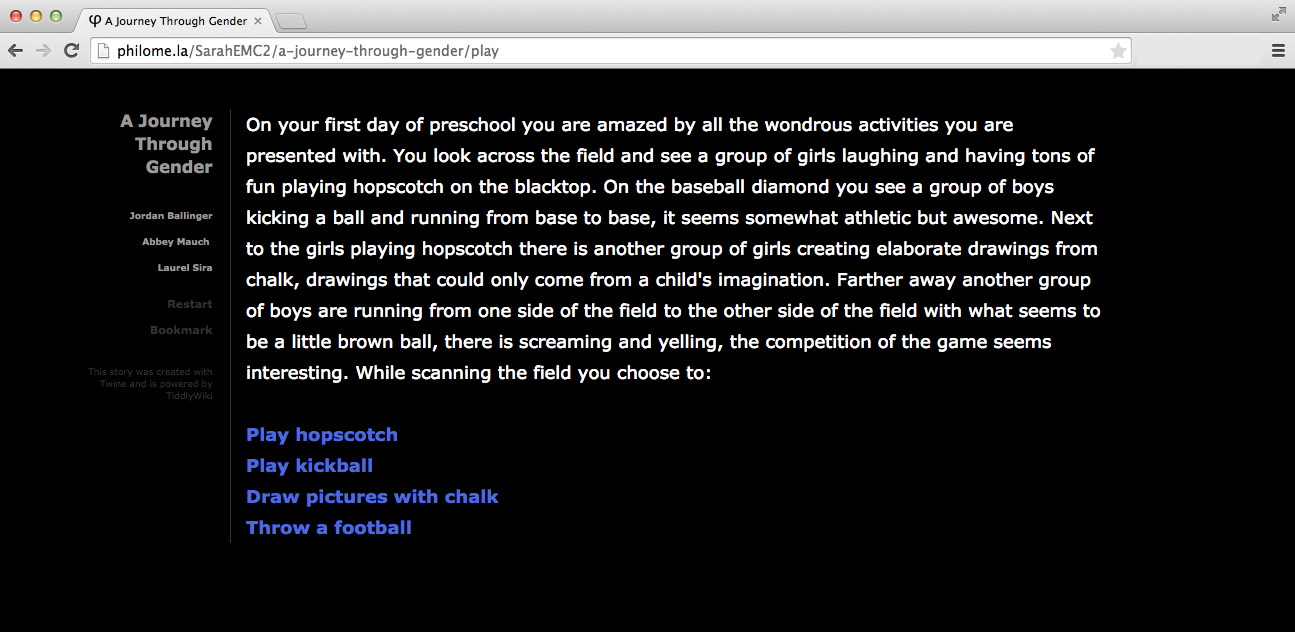

We received many strong games in response to this assignment, but one of our favorites focused on the lived experience of gender and gender variance created by Jordan Ballinger, Abbey Mauch, and Laurel Sira. The game provides users with a complex set of choices that represent un/expected gendered behaviors at various points in childhood. Entitled “A Journey Through Gender,” the game allows for a variety of gender expressions without ever forcing the player into a fixed gender identity. The interactions available to the player are complex and the available choices are meaningful. What emerges, then, is not a dialectic on gender but an exploration of it in which both the authors and the players are participating in a complex discourse about the construction of gender across childhood and into early adulthood.

In reflecting on the development of this game, the students–who identified as cisgendered men and women–said that both the pre-drafting exercises and the development of the game created for them a more nuanced and complex understanding of the ways in which gendered behavior is policed in early childhood and adolescence in order to enforce gender conformity, and each was able to identify moments in their own life in which they had transgressed assigned gender roles and been corrected by parents or peers. They chose to create the game around those experiences to demonstrate the emotional and psychological impact of that policing. Their goal–which we feel they achieved–was to provide the player with the experience of having gender non-conforming behaviors create some (but not an unreasonable amount of) tension with the social systems in which the player character operated, and to form a subtle argument against the enforcement–formal and informal–of gendered behaviors.

The Assignment

link to assignment pdf: Einstein & Vetter Twine Game Assignment

While planning how to incorporate Gamergate readings into our class, we realized that Twine itself could be a powerful tool for exploring audience, exigency, research, and argument. Twine games are essentially “choose your own adventure” texts, and are easily created using free software. We assigned groups of students to work together to create a Twine game that explored a social issue relevant to the topic of the course and designed to provide the player with the opportunity to explore that issue from a stakeholder perspective. It was key to the assignment that the player character have meaningful choices that lead to a variety of outcomes…in other words, that the player have agency within the game, and that the decisions made by the player could lead to desirable or undesirable results. Students created games on topics such as street harassment, coming out as queer at college, and sexual assault at Ohio University.

The project began with an annotated bibliography, which was to include both academic sources and online texts written by stakeholders. Research was a key component to this project, because–like all of us–students brought with them their own mis/understandings of both the issues they chose to explore and the positionality of the stakeholders in that issue. The groups then used this information to create games that provided the user with distinct ways to navigate the social issue, leading to either desirable or undesirable outcomes.

Choice and Non-Choice in Narrative Games

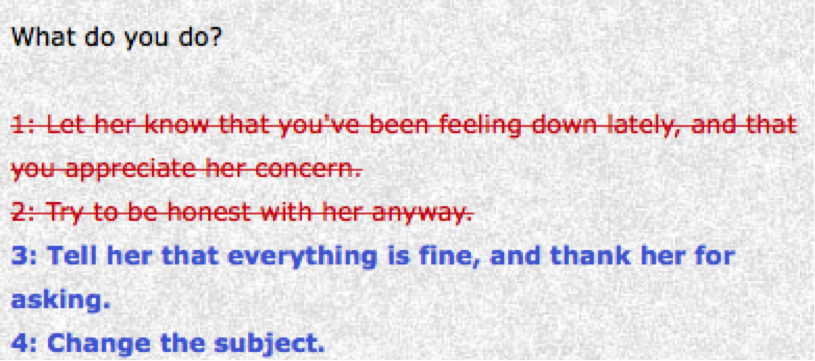

A particularly powerful device in Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest is her use of “non-choice” as a mode of description that transcends the game’s narrative to invoke the experience of depression. As a “gamebook,” Depression Quest allows the reader/player to choose between different options that progress the narrative among different paths. But Quinn takes this idea further by including in these options, choices that are also crossed out or negated. In screen after screen, the player is presented with choices that, because of the debilitating effects of mental illness, are simply not viable.

The effect of this device on the player is striking. It is a “closing down” – a sense of tunnel existence in which we feel (or re-feel if the player has previous experience with depression) the very trapped-ness and sadness, there’s no other way of putting it, of mental illness.

Because of our culture’s stigmatization and marginalization of mental disability, individuals suffering from mental illness experience less choice, and less agency, than those who do not suffer from mental illness. In our exploration of gender and sexuality in this course, we also began to view the trope of non-choice as a productive heuristic for the interrogation of gender and sexuality hegemonies. In the screenshot above, the speaker confronts the difficulty of disclosing her depression to a family member. Those choices that would allow for disclosure are crossed out, emphasizing the lack of choice the speaker has to confess to and accept the stigma associated with mental illness, to”come out” as mentally ill.

Experiencing this scenario in a narrative game about depression allowed for students to also consider the intersectionalities between mental illness and the circumstances facing individuals who cannot or refuse to accept heteronormative notions of gender and/or sexuality. The sexual and gender binaries of hetero-patriarchies prohibit and constrain the choices and agencies of individuals outside those binaries. Reflecting on the choice or lack of choice that Western cultures present us with became, for both students and instructors, a powerful way to understand intersections between mental illness, gender, and sexuality, as well as the ways in which mainstream game genres have failed to challenge these constructions.

Choose Your Own Adventure

Twine turned out to be an excellent way for us to engage gender politics, identity, and narrative in the writing classroom, especially as part of a larger curricular unit that examined the politics of #Gamergate, videogames, and women writing in digital spaces. But we also recognize that we’ve only begun to imagine additional ways that Twine, as an “open-source tool for telling interactive, nonlinear stories,” might be used for other goals and in other scholarly, educational and creative contexts. As a form of new media that remediates “gamebook” or “Choose Your Own Adventure” genres, Twine also opens up new modes of narrative expression and form, and does so through a free and open source ethic that encourages appropriation, remix, sharing, and creative adaption. Such an ethic begs the question: What else can we do with this software? What will you do with it? Tell us in the comments section below.

1 Comment

#Gamergate is not in support of a gaming world that is devoid of women, a female perspective, trans developers, or harassment. Simply a world where a creator can make a product and not have legions of easily offended adults demand an artist to change their vision. A world that holds gaming journalists to the same standards of critics from other art forms without collusion.

Yes, there are trolls out there. It was painfully easy for anonymous people to pervert the message most of us had intended, so much so that we have no way to show people what we actually wanted. They would rather just “listen and believe” in their world where no one ever is shown a different viewpoint.

But there’s no way to convince anyone I’m not a monster, because I’m a white male.