Visualizing the Archive

TRENDS ACROSS THE CORPUS

Production vs. Reception Timeline

Instructions: Click legend below the graph to turn lines on and off. Double click or pinch graph to zoom in. Drag graph to move through time.

X = year; Y = number of articles

-

Click to view graph data in table format

Articles by Year Table

Year Production Reception All 1912 0 1 1 1913 1 1 1 1914 1 0 1 1915 3 4 6 1916 1 1 2 1917 1 2 1 1918 1 1 1 1919 1 0 1 1920 0 0 0 1921 0 0 0 1922 0 2 6 1923 4 1 1 1924 0 1 3 1925 2 0 2 1926 2 0 1 1927 1 0 1 1928 2 1 3 1929 2 0 1 1930 1 0 1 1931 1 3 6 1932 4 6 8 1933 2 3 6 1934 4 6 7 1935 1 5 7 1936 5 5 5 1937 0 7 14 1938 8 5 8 1939 3 10 19 1940 12 8 12 1941 4 4 10 1942 6 3 8 1943 5 2 4 1944 2 1 1 1945 0 1 4 1946 3 7 8 1947 1 3 3 1948 0 9 13 1949 4 6 9 1950 3 6 8 1951 2 10 13 1952 3 8 11 1953 3 6 7 1954 1 8 11 1955 3 2 3 1956 1 2 3 1957 1 3 4 1958 1 5 5 1959 0 3 6 1960 3 5 5 1961 0 8 9 1962 1 6 6 1963 0 7 9 1964 2 6 6 1965 0 5 5 1966 0 3 4 1967 1 4 8 1968 4 11 14 1969 3 1 2 1970 1 2 5 1971 3 4 11 1972 7 4 7 1973 3 2 7 1974 5 9 15 1975 6 6 6 1976 1 3 11 1977 8 6 8 1978 2 4 5 1979 1 7 8 1980 1 6 8 1981 2 6 12 1982 6 2 7 1983 4 5 11 1984 6 5 17 1985 12 7 13 1986 6 5 10 1987 5 6 13 1988 7 4 14 1989 10 5 13 1990 8 4 7 1991 3 3 6 1992 3 5 5 1993 4 4 7 1994 7 3 10 1995 16 6 22 1996 5 3 7 1997 6 3 9 1998 9 11 20 1999 5 5 10 2000 20 2 21 2001 5 2 6 2002 6 5 11 2003 5 4 9 2004 6 2 8 2005 5 1 6 2006 2 2 4 2007 10 9 17 2008 4 2 6 2009 2 6 8 2010 15 5 20 2011 7 1 8 2012 11 3 14

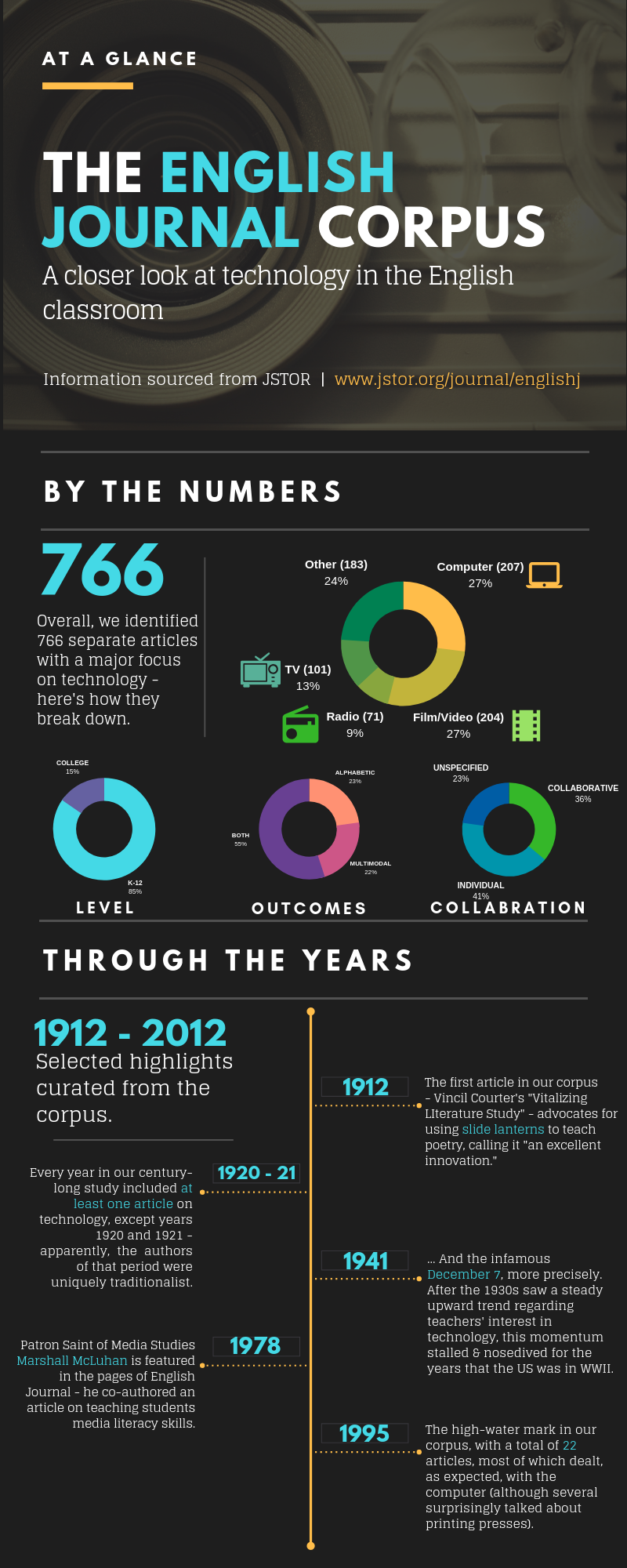

As you click the legend to turn the lines on and off or double click the graph to zoom in on years of interest, stay alert to what patterns you can observe occurring over time. As you look at the “all articles” timeline, you’ll note that English pedagogy has long been concerned with diverse forms of media beyond the print book. Although some of the greatest peaks in new media interest occurred in the past two decades, we found media-related articles in every year except for 1920 and 1921. As you turn on the lines dedicated to production and reception pedagogies respectively, you can note that media reception tended to predominate over media production in most years until the 1980s, the era of the personal computer; however, there was a brief spike in media production pedagogies in the 1930s when sound film and radio were quite new, as well as a minor spike in the early 1970s when new forms of multimedia equipment proliferated the consumer market. We note with interest that the late 1930s and early 1970s spikes in media production pedagogy also coincided with time periods that featured robust leftist social movements and corresponding emphasis on “progressive,” student-centered pedagogies. As we zoom in on specific media in the next section, we’ll start to outline more interpretations of why and when media production pedagogies tend to wax and wane. For now, we offer two preliminary observations: (1) media production pedagogies appear to have a very long history in English studies (indeed we coded over 356 articles featuring media production pedagogy, including 145 before 1980); and (2) the computer era has coincided with a rise in media production pedagogies.

Production vs. Reception Donut Chart

Instructions: Click the radio buttons below to view production vs. reception counts for the four most prominent media in the corpus.

-

Click to view graph data in table format

Production vs. Reception by Media

All Radio Film Computer Production 364 29 50 157 Reception 401 42 154 50

As you play with the donut chart, you can see that production has only very slightly predominated over reception in the corpus. As we look at specific media, we can uncover a substantial tradition of production pedagogies in relation to radio, film, and video—a tradition that predates the personal computer. When you select the button for television, you can see that reception pedagogies occur much more frequently than production when it came to this particular medium, making us begin to wonder why teachers tended to see TV primarily as an object for critique and analysis. In contrast, when we turn to computer, we see a radical shift whereby production-oriented pedagogies radically outnumber reception pedagogies, offering further evidence to support our hunch that the computer truly has been a disruptive force in English pedagogies.

Gender of Authors: Production vs. Reception Donut Chart

Instructions: Click the radio buttons below to view production vs. reception counts by gender of author in the corpus.

-

Click to view graph data in table format

Gender of Authors Table

All Production Reception Women 333 195 138 Men 353 152 220 Multiple Gender 44 25 19

As we discussed in the methodology chapter, our coding of author gender was necessarily imprecise as we had to make our “best guess” based on author first names since it was not practical to ask authors from long ago how they self-identity on the gender spectrum. Moreover, to reduce noise, we excluded articles that had no clear attribution (e.g., no byline, corporate author). Nevertheless, we find that our speculative, limited coding of gender author reveals some interesting trends. First, it is important to note that women authors have long been a strong presence on the pages of English Journal—nearly as prominent as men. Furthermore, women authors composed the majority of the production-focused articles in the corpus by a rather large margin. It is also particularly noteworthy that women teachers’ tradition of technological making extends well before the digital age, as you’ll see in our case studies of 1930s radio and film production pedagogies in chapters 4 and 5. While more women authors displayed interest in collaboratively engaging students in making their own media, it appears that more male teachers focused on “explaining” new media to students as if they didn’t already understand them. We might suggest then that the English Journal archive can contribute both to a history of “mansplaining” as well as to the broader feminist effort to recover women’s histories of technological making (Blair 2019; Good 2020).

Topoi for Teaching “New Media”

X = number of articles; Y = topoi

-

Click to view graph data in table format

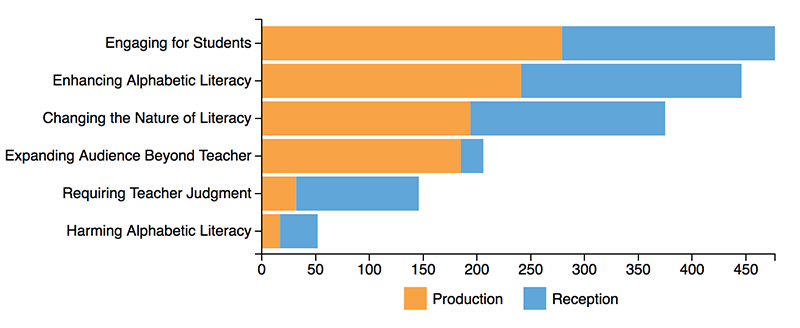

Topoi for Teaching “New Media”

Topos Production Reception Engaging for Students 279 198 Enhancing Alphabetic Literacy 241 205 Changing the Nature of Literacy 194 181 Expanding Audience Beyond Teacher 185 21 Requiring Teacher Judgment 32 114 Harming Alphabetic Literacy 17 35

As you peruse the bar graph and table to see the total number of articles that included a particular topos, you can note how the claim that new media are “engaging for students” was pervasive throughout the corpus (indeed, 477 articles made some form of this claim, including 241 articles before 1980). The second most prevalent topos we found was the claim that new technologies could be used to “enhance the teaching of alphabetic literacy” (n = 466). Often, we found that the the topoi of “engagement” and “enhancing alphabetic literacy” co-occurred in articles; for examples, we found these linked topoi in articles that claimed students would become more engaged with alphabetic reading and/or writing if they listened to Shakespeare on the radio (Carney 1938), if they made film adaptations of classic poems (Hodge 1938), or if they revised alphabetic essays with computers (Monahan 1982). In this way, we can see that English teachers have tended to focus perhaps too narrowly on articulating how new media could be used to enhance alphabetic literacy instruction.

Despite the tendency to imagine new media first and foremost as serving alphabetic learning goals, the articles in our corpus also frequently promoted the commonplace assumption that new media were “changing the nature of literacy” itself (n = 375)—often pointing out how the arrival of a new medium required that English teachers pay more attention to the unique affordances of visual, multimedia, and audio forms of communication. As we unpack the apparent contradictions in the top three most prevalent topoi in our corpus, we can gain a sense that new media have been a source of ambivalence and tension in the field over time: on the one hand, English teachers have sought to harness new media to teach traditional alphabetic reading and writing skills while also paradoxically engaging new media as a heuristic to rethink what the teaching of literacy entails. We see similar tensions and ambivalences at play in contemporary scholarship on digital composition (including our own). We find ourselves humbled when we come to recognize that many of the claims we have made about digital and multimodal pedagogies turn out to be very old indeed.

When we began this project, we expected to find many articles in which English teachers bemoaned how new media were harming students’ alphabetic literacy skills, yet this turned out to be a relatively rare topos in our corpus (n = 52). Although we might be tempted to conclude that the field of English as a whole has always been welcoming to new media, we should of course remember that English Journal offers a relatively narrow view of the field. Because the primary mission of English Journal has been publishing innovative scholarship about K-12 English pedagogy, it makes sense that it has tended to privilege articles that emphasized how new technologies could enhance learning rather than screeds about the need to stick with tradition.

When we zoomed in to look at how these topoi were distributed in articles about production pedagogy compared to articles about reception pedagogy, we found some interesting divergences. Although the argument that new media can “expand audiences beyond the teacher” was quite common in articles about media production (n = 185), it was relatively rare in articles about media reception (n = 21). In this sense, we can see that media production pedagogies have tended to disrupt traditional models in which students compose primarily for the purpose of teacher evaluation. Conversely, the argument that new media “required the aesthetic and/or moral judgment of the teacher” was much more common in articles about teaching media reception (n = 144) than in articles about media production (n = 32).

In analyzing the prevalence of the “teacher judgment” topos in reception articles, we should keep in mind that the cultural construction of the English teacher as arbiter of aesthetic taste and moral virtue has a long history—especially in relation to the teaching of literary analysis (Applebee 1974; Berlin 1984). Given this legacy, it’s not surprising that English teachers often sought to position themselves as belletristic authority figures whose duty was to carefully guide students’ radio, television, and film consumption (Carney 1938; Hodge 1938; Orndorff 1939). By contrast, when English teachers turned their attention to teaching students to compose with new media, they were less likely to conceptualize their work in relation to the belletristic tradition. We surmise that production pedagogies did not emphasize teacher judgment as frequently because teaching new media composing often placed English teachers in a position in which they did not feel like an expert authority—a position in which they may even have needed to turn to students for technological advice and support. As a result, media production pedagogies have tended to place less emphasis on the importance of the teacher’s value judgment and more emphasis on the transformative potential of students composing texts for “audiences beyond the teacher,” including fellow classmates. In this way, we can begin to speculate that media production pedagogies have been (at times) a resistant force, which has challenged conventional ideologies of teacher authority in English instruction.