Re-Seeing Film and Video Pedagogies

Super 8 and Camcorder Fun

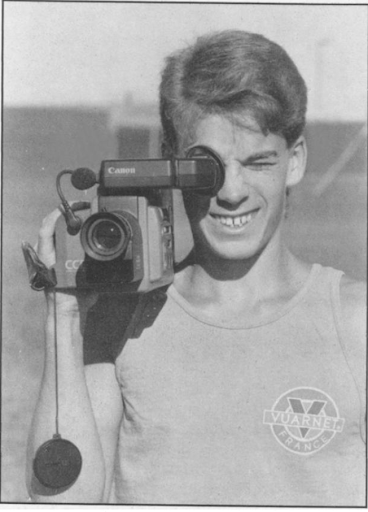

After the boom in student film production in the late 1930s and early 1940s, English teachers increasingly positioned films solely as objects for analysis throughout the mid-century period. Indeed, we found zero production-oriented film articles from 1943 through 1966—though we coded numerous articles focused on film reception in this era. Starting in 1967, film production pedagogies picked up again, as teachers were increasingly inspired by the development of the Kodak Super 8 and other inexpensive 8mm cameras to once again position moviemaking as part of the work of the English class. This trend would extend into the later seventies and eighties, as the rise of the consumer video camcorder also produced an uptick, albeit a more modest one, in discussions of cinematic production in the journal.

As we perused English Journal issues from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, we found numerous vivid descriptions of student film and video projects in diverse genres. While we have been unable to locate these original student films, we have attempted to bring these student projects back to cinematic life by composing mock video trailers for selected student projects described on the pages of English Journal. Although our trailers attempt as much as possible to stay true to the spirit of student film and video production as described in the archive, these trailers also necessarily involve substantial creative reinvention and flights of fancy. Readers seeking a more faithful accounting of student film production in this period should consult the text below.

-

Click to view transcript

The Best of Student Films, Volume 1 (.txt version)

[Video: FBI Copyright warning]

[Audio: generic 1980s-era elevator music]

[Video: title reads “The Best of Student Films, Volume 1”; background of eighties neon grid-styled landscape]

Announcer: Coming soon to home video, it’s The Best of Student Films, Volume One. On this cassette, we bring you a collection of never-before-seen gems for classroom viewing. From Super 8 to VHS, these student productions from over the past several decades are sure to inspire your English class to make their own cinematic masterpieces. So let’s take a look at what’s inside.

[Video: Image of Rated G trailer screen]

[Audio: somber piano music throughout segment]

[Video: text on screen reads “Produced by Kirkwood High School AP English, Kirkwood Missouri—1971”]

[Video: clip of hermit crabs on beach]

Voiceover: I should have been a pair of ragged claws. Scuttling across the floors of silent seas.

[Video: clip of yellow cat stretching on yellow backlit window ledge]

Voiceover: The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes. The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes.

[Video: clip of bare feet walking on beach and leaving footprints]

Voiceover: I grow old . . . I grow old . . . I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

[Video: title reads “Prufrock / Based on the Classic Poem by T.S. Elliot”]

[Video: image of Rated R trailer screen]

[Audio: classic rock music]

[Video: Title screen reads “What’s Happening at Rocky High”]

Voiceover: Here at Rocky High, there’s so much going on behind the scenes—let’s take a peek.

[Video: clip of marching band practicing; text on screen reads “Band Shenanigans”]

[Audio: up tempo band music]

[Video: clip of football players practicing; text on screen reads “A Football Stadium in Shambles”]

[Audio: classic striptease soundtrack]

[Video: clip featuring arms of women wearing white uniforms dishing out mashed potatoes onto plates in cafeteria; text on screen reads “Lustful Lunch Ladies!”]

[Audio: somber piano music]

[Video: clip depicts spinning game wheel landing between two supposedly divergent life paths, “get stoned” and “win scholarship”; text on screen reads “Learning the Dangers of Dope”]

[Video: clip of hippie teens conversing and looking too happy]

[Audio: triumphant film score]

[Video: clip of several men running towards table, who then sit and begin to eat pies vigorously; text on screen reads “Varsity Pie-Eating Team”]

[Video: clip of band practicing; text on screen reads “Stories Galore”]

Voiceover: Rocky High Class of 76 rules!

[Video: image of Rated G trailer screen]

[Video: text on screen reads “An Opportunity Scholars Production: University of South Carolina”]

Voiceover: Growing up in the South it ain’t exactly easy, but I’ll tell you what, I wouldn’t want to live any other place . . .

[Audio: Classic Appalachian Folk Song]

[Video: several shots of landscape of rural South; transition to text on screen reading “Winner 1976 Documentary Film Festival”]

[Video: shot of horse-drawn plow fades into shot of mechanical tractor; cut to clips of children and farm animals]

[Video: Title screen reads “Southern Stories: A Documentary Series”]

[Video: text on screen reads “Never-Before-Seen-Interviews”; clip of older Gullah woman speaking, followed by older white woman speaking]

[Video: text on screen reads “Historical Roots”; shots of white people weaving, playing fiddles, and square dancing] [Video: text on screen reads “Original Performances”; clip of younger Black woman performing a solo modern dance.]

[Video: clip of a young multicultural choir singing in unison; Text on screen reads “Teaching the World to Sing . . . / . . . In Perfect Harmony”]

[Video: Text on screen reads “Coming Soon”]

[Video: image of Rated G trailer screen]

[Audio: Eighties synthesizer music plays throughout segment]

[Video: hand-drawn animation of orange rocket with young male orange astronaut inside; the rocket flies onto screen and the astronaut floats outside; a comic bubble reads “I have to save the universe!”]

[Video: hand-drawn animation of blue rocket with young male blue astronaut inside; the rocket flies onto screen and the astronaut floats outside; a comic bubble reds “No, I have to save the universe!”]

[Video: blue and orange astronauts appear on screen together; comic bubble reds “Why don’t we save it . . . together!!!”]

[Video: title screen reads “Cosmic Kids”; followed by text on screen reading “Sacred Heart High School. Nominated for a Judy Award (1984)”]

[Audio: generic 1980s-era elevator music]

[Video: title reads “The Best of Student Films, Volume 1”; background of eighties neon grid-styled landscape]

Announcer: You’ll find all this and more on The Best of Student Films, Volume One. Here’s what some prominent educators have been saying about this collection.

[Video: text on screen reads “‘The Benefits of this project lie in the fact that each student thought originally, creatively, and clearly’ (125)—Jeanette Hanke”]

[Video: text on screen reads “‘Film has the power to make us feel. But in addition film study generates language and literature learning of a high order which to me is its own justification in the English Class.’ (50)—Carole Cox”]

Announcer: That’s The Best of Student Films, Volume One. Order yourself a copy today.

[Video: text on screen reads “Order Now 1-800-867-5309 CC 100 Years Productions”]

Media assets used in this production listed in Production Notes.

The 1960s witnessed a proliferation of consumer-oriented film cameras, including the famed Kodak Super 8, which debuted in 1965. Although film equipment was less expensive in this period than in the 1930s, cost remained a concern, and teachers and students employed a wide range of tactics and hacks to gain access to the means of cinematic production. As we survey the varied landscape of student film and, later, video production in the sixties, seventies, and eighties, we find a complex mix of transgressive possibilities and exclusionary limitations that cannot easily be woven into a seamless narrative. Accordingly, we present here a series of snapshots of the highly varied approaches we found to moving image production in English classrooms in this tumultuous era, organized simply in chronological fashion.

In 1967, film production burst back on to the pages of English Journal with the publication of David Babcock’s “A Way to Inexpensive Movie Making.” In this article, Babcock suggested that English teachers could gain access to film cameras by borrowing “cameras bought by well-meaning Booster Clubs for filming sporting events” (469)—thus finding a creative way to siphon funds from athletics to the humanities. While Babcock categorized his pedagogical work as moviemaking (and we likewise coded it accordingly), his filmmaking project focused primarily on teaching students to make film parodies of television commercials as part of a unit on propaganda. By engaging students in making rhetorical choices in filming their own commercials, Babcock hoped to help them become more critically aware of the media-specific manipulations that typically occur in visual media.

In contrast to Babcock’s suggestion of borrowing film equipment from booster clubs, an article by Peter Dart in 1968 made the case that film equipment should be purchased as part of regular instructional budgets, noting that “a simple eight-millimeter camera costs less than $20.00. Four minutes of an ‘off-brand’ color film, including processing, can be purchased for about $2.00. [. . .] With or without federal funds, most school systems can afford simple eight-millimeter equipment” (96). We find Dart’s comments on affordability to be overly optimistic in light of inequalities in school funding, as well as the tendency of administrators to view film production equipment as an unnecessary expense. Nevertheless, Dart’s assertion that the rise of lower-cost 8mm cameras provided a new exigency for filmmaking pedagogies in English classrooms was a common one in the period. In making the case for the pedagogical value of moviemaking, Dart argued that filmmaking projects could enhance students’ ability to learn how to make reflective rhetorical choices for audiences. Highlighting the unique affordances of cinematic versus alphabetic composing, Dart proclaimed: “How many student papers are eagerly sought to be read by other students? Almost any student film can find an immediate, enthusiastic, and critical audience” (97). To this end, Dart suggested that students should seek feedback on their films from multiple peer audiences, both inside and outside of class. In order to spur rhetorical reflection, Dart advised that teachers ask the student “to justify what he did, or explain what he would like to have done” (98)—offering reflective prompts that remain common in multimodal pedagogy today (though with more gender inclusive language, we hope).

While Dart and Babcock looked towards contemporary film and television genres for inspiration for student filmmaking work, some 1970s teachers continued the older 1930s tradition of engaging students in making film adaptations of literary classics they were reading (Hanke 1971; Mulherin 1973; O’Keefe 1971). For example, Jeanette Hanke reported on an AP English class project in which students created a film adaption of T. S. Eliot’s poem, “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Hanke’s students raised money for film equipment by holding a bake sale and seeking additional donations from parents and local business owners. Although Hanke’s Missouri students lived far from the sea shore, they still managed to create images of muddied footprints on a local “beach,” and one particularly ambitious student with money to spend even went so far as to telephone “a company in Florida to airmail two hermit crabs for the ragged claws image” (Hanke 1971, 123). Once again, as in the 1930s, we noted the expenses of student film production being borne mostly by class-privileged students rather than by sustainable and equitable sources of public funding.

In another example of literary film adaptation pedagogy, Patrick O’Keefe (1971) reported success in engaging an unenthused group of high school students in making a cinematic version of Shirley Jackson’s famed story, “The Lottery,” a project that relied on a Super 8 camera loaned by the father of one of his students. While O’Keefe made a good case that collaborative filmmaking projects could be a great way to engage students in reading and writing for real audiences, his practice of assigning students to groups based on “ability” problematically limited the learning potential of his filmmaking project. Implementing a product-centered, hierarchical approach to guiding collaboration, O’Keefe “selected the better writers and ‘idea people’ to sit together and write the script” while he “urged three academically ‘poor’ students to be cameramen” (958). Rather than employing film scripting as a way to engage these less successful students in learning writing, O’Keefe chose to remove them from the work of writing altogether. While these young cameramen no doubt learned valuable skills in cinematography, they also received a strong and problematic message that writing was simply not for them.

As the 1970s came into full swing, we started to see evidence that filmmaking was moving from an ancillary activity to a central part of the English curriculum in at least a few schools. In 1974, Alma Reinecke reported on how student filmmaking was integrated across the entire ninth grade English curriculum at her Sioux Falls Junior High School, using 8mm film equipment supplied by the school district’s Audio-Visual department (Reinecke, 71). Reinecke was deeply committed to giving students the choice of topic and genre for the films they made, and students produced a variety of fiction and nonfiction films telling stories that reflected their own personal interests. In justifying her decision to leave choices of film topic and genre largely open, Reinecke specifically critiqued the tendency of English teachers to position filmmaking solely as a way to teach literature and writing:

Sometimes teachers feel that filmmaking can only be justified if it will motivate students to read or to write. The instructions to the students go something like this: “You will have to read all of these short stories and several of these poems to get a plot or idea for a movie. Then each one of you will write a scenario and we’ll select the best one. Then after we’ve made the movie, we’ll write criticisms about it.” I suggest that you not try to unload your other English burdens onto this project. We have already turned off enough kids to reading by requiring a written book report for every book they read, and we have discouraged them from writing with enjoyment by insisting they imitate paragraphs written for composition books. We can easily get them to hate making movies as well. (71)

For Reinecke, filmmaking was a valuable English class activity in and of itself. The desired outcome of student filmmaking in her class was not to improve students’ traditional alphabetic reading and writing, but rather to enhance their ability to analyze and compose films as a uniquely valuable medium distinct from print literature. We like Reinecke’s central argument in this article: we must vigilantly guard against the perennial risk that English teachers can make any kind of new media composing seem dull to students if they unduly constrain students’ ability to take advantage of the unique affordances of a new medium to pursue their own goals.

In addition to challenging the tendency of teachers to approach filmmaking in limiting ways, Reinecke also critiqued the tendency of film scholars to devalue amateur 8mm production. In fact, Reinecke opened her article by recounting the story of noted film scholar at an academic conference who pronounced: “‘From the 8 millimeter mind God in his heaven protect us!’ He believed that if filmmaking is to be taught in the schools, it should be done in 16mm, 35mm, or not at all” (Reinecke, 70). In response to this claim, Reinecke noted that 8mm film was the only economically practical way to integrate filmmaking into secondary English education, and that such work was vital if schools were to succeed in teaching students to critically engage the increasingly powerful medium of film. Challenging the common assumption that students could learn about film simply by watching and analyzing professional 35mm films made by famed auteurs, Reinecke asserted, “It has been the experience of many teachers that students learn more about film through the activity of making one than through many hours of passive viewing” (70). For Reinecke, 8mm filmmaking (supported by public funds, we should note) provided a useful way to engage all English students in developing cinematic literacy, and she therefore resisted the cultural pressures to reserve the act of filmmaking solely for professionals who could afford 35mm equipment.

In another example of student-centered media production, Charles Oestreich (1974) recounted the story of an elective English class at Rock Island High School—colloquially known as “Rocky”—that made a weekly series of short films about life at the school. While they covered some more investigative topics such as the need for repairs in the football stadium or the school’s program of drug education, students also covered more humorous stories such as pie-eating contests. At times, the student-centered nature of the broadcasts led to some problematic humor. For example, in a documentary about the school lunch program, students included footage in which the “cafeteria ladies baked scalloped potatoes to a soundtrack of striptease music”—though the article does not mention if the women in question were aware of how their images were to be used. Although we appreciate that Rocky High students were given a lot of freedom to choose their own topics for film, the story of the striptease soundtrack reminds us that students still need direct instruction in critiquing and avoiding sexist tropes of dominant media production.

While Oestreich largely restricted students to making documentaries about school-related topics, other teachers such as Helen Foley engaged students in composing community-oriented documentary films. In 1971, Helen Foley detailed an extensive project in which Houston-area high school teachers collaborated with the media center of Rice University in order to teach students to compose poetic documentaries about aspects of life in their city. This collaboration with the Rice University media center not only provided students with technical assistance, but also with the opportunity to receive rhetorical advice from prestigious visiting filmmakers. For Foley, one of the greatest benefits of teaching students to make documentary films was that it helped them learn how to make reflective rhetorical choices of composition that could then transfer back to their work with writing. In particular, Foley recounted that when her class returned to writing after finishing their films, they viewed their own writerly choices in a new cinematic light:

The students had assimilated through filmmaking another language, one that they could relate to their written language. They told me that when they tried to describe a place or character, they simply visualized how they would frame the subject, how they would move the camera. When they had to deal with problems of order, arrangement, and selection, they remembered how they had edited their films to impose a shape or form. They became as intoxicated with words as they had been with film. (Foley 1971, 1108)

While recognizing that film and alphabetic writing were different languages, Foley still suggested that there were potential similarities in the kinds of rhetorical choices that filmmakers and writers made. In particular, Foley wisely pointed out that experience with nonlinear film editing might help students rhetorically explore more options for rearranging their words outside of the order in which they were originally composed. We find it particularly noteworthy here that Foley positioned filmmaking not simply as a way to interest students in learning traditional writing, but rather as a way to help students reimagine and extend their own composing processes in creative ways.

In another example of collaborative student documentary filmmaking, Nancy Cromer (1976) wrote of first-year composition class project at the University of South Carolina in which a class collaborated on a video project about “living in the South” (94) that they then exchanged with a class at Queens College in New York City. Cromer’s class was part of the Opportunity Scholars program and included a diverse group of Black, white, and Asian American students. The students’ collaboratively produced videotape included footage of discussions among themselves about race relations in the South, interviews with older residents of a nearby small town about their experiences growing up in the South, and an original solo dance performance by a Black woman in the class. The videotape finished with “the whole production crew singing the UNICEF peace song that was made famous by a Coke commercial, ‘I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing in Perfect Harmony’” (Cromer 1976, 94).

Although we see value in Cromer’s goal of having students make documentary films about issues in their lives, we also can see how the potentially transformative power of the filmmaking project was unduly constrained by ideologies of “color-blindness” (Lamos 2011) that limited students’ opportunity to engage critically with racist power structures. Failing to account for differences in racial privilege among students, Cromer emphasized that class discussions about race would be governed by the dictum that they “would try to understand the other person rather than try to change him” (94)—a guideline that put students of color in the oppressive position of being taught to attempt to empathize with racist ideologies expressed by white students. Instead of learning to interrogate and challenge unequal structures of racism, Cromer’s students instead reported learning how to have a respectful dialogue about how both white and Black students were “prejudiced toward each other without worrying that a fight may break out” (95). In this way, we can see that the students’ filmed conversations on race were unduly limited by a frame that emphasized individual bias rather than challenging and undoing racist power structures. Furthermore, despite the fact that Cromer’s article was published two years after the “Students’ Right to Their Own Language” resolution, her class emphasized teaching Standard English and (as far as we can tell) did not include discussion of the racial politics of linguistic diversity.

Strongly reinforcing Standardized English ideology, Cromer closed her article with a quote from a student, whose race was not identified, reporting that the video project had taught him to practice “using standard English, and this strongly affected my ability to express myself” (95). By concluding the article on this note, Cromer suggested that perhaps the greatest value of video production in English classes was that it could motivate students to learn to speak and write Standard English following the norms of whitestream media. Instead of considering ways that collaborative video production might enable students to critically interrogate questions of race and racism (Kinloch 2012), Cromer ended up using video, at least in part, as a tool to reinforce dominant rhetorics of color-blindness and Standard English hegemony.

Film and Video Production in the 1980s

As the 1980s rolled in, a small number of English teachers continued to experiment with moving image production in their classes using a diverse mix of consumer-oriented film and video equipment. While the 1970s saw teachers making the case that filmmaking should play an increasingly large role in the core English class, English teachers in the 1980s tended to suggest that filmmaking should be reserved for special elective classes (Cox 1984; Wyatt 1981) or should be placed in service of academic research writing (Mikulec 1984; Urban 1989). Revealing the rhetorics of accountability and austerity that influenced media production pedagogies in the 1980s, Helen Wyatt began a 1981 article about her filmmaking elective course at a high school in Kansas by noting that parents often “wonder whether the course is one of those frills taxpayers complain about. Most would be surprised to learn that it had made students want to master basic English skills” (103). Wyatt’s filmmaking class started by engaging students in analyzing a mix of professional and student films. Students then formed “mini-production companies” (103) and made their own films through a scaffolded process of storyboarding, shooting, and editing in dialogue with regular feedback from peers and instructor. In many cases, students made documentary films about local issues including the need for a school soccer program or the risks of football injuries. In making the case for how filmmaking could enhance basic English skills, Wyatt somewhat problematically suggested that filmmaking be positioned as a kind of reward for students: that students be told that they could not “progress to [filmmaking] lab projects until they have mastered certain assignments in reading and writing” (103). Instead of considering more fully how alphabetic literacy and filmmaking might be more seamlessly integrated to enhance student engagement, Wyatt implicitly positioned alphabetic literacy work as the drudgery that students had to endure to get to the fun of filmmaking—a tactic that risked further disengaging students from writing while also reinforcing the problematic assumption that filmmaking was ancillary to the real work of the English class.

While the rhetoric of placing film in service of basic skills was strong in the 1980s, a few English teachers continued to make the case that moviemaking was valuable in its own right. For example, Carole Cox opened her 1984 English Journal article about an elective filmmaking class by explicitly cautioning readers that “rather than set forth a rationale, I will assume that anyone reading this is already interested in the potential of filmmaking or has tried it and would like to compare notes” (46). We applaud Cox’s radical rhetorical refusal to focus on justifying media production work in terms of conventional literacy outcomes—though we recognize that this rhetorical move also problematically narrowed her audience. Cox organized her filmmaking course by having students watch films about the filmmaking process, individually brainstorm ideas for their own films, and then brainstorm together to develop small-group, film production teams. Once the teams were established, students then went through a collaborative process of composing scripts and storyboards, and then finally shooting and editing.

Although Cox presented the stages of the filmmaking process in a somewhat linear fashion, she also pointedly argued that recursive (re)invention and reflective writing should be integrated throughout that process. To this end, each individual student kept a filmmaking diary in which they discussed their ideas for and thoughts about the filmmaking process. In describing the value of these diaries, Cox wrote:

These filmmaking diaries increased geometrically throughout the semester. Filmmaking is an organic activity that has a tendency to grow tentacles. Students seem to be constantly wrestling with a new idea or image, rethinking and revising an old one, or pushing their visions just one step further. (46–47)

Cox reported that the filmmaking diaries were especially helpful during her conferences with students, as they enabled them to have deep conversations about their rhetorical choices and evolving goals as filmmakers. Cox’s students produced a wide diversity of film types. Projects ranged from an original live-action film adaptation of a novel, to a documentary about the school football team, to a cut-out animation space odyssey entitled Cosmic Kids. The students were particularly motivated to work hard on their films, as they knew that they would be screened at a school-wide Sacred Heart film festival where they had the opportunity to be selected for a competitive “Judy Award” (named after Sister Judy, the school principal who greenlighted the elective filmmaking class).

While Cox’s article offered an inspiring model of student-centered, process-based filmmaking pedagogy, her approach appeared not to have much uptake in the 1980s, as teachers increasingly came to position the emerging technology of the video camcorder solely as a tool to supplement traditional writing instruction. For example, in a 1984 article on “Video-English,” Patrick Mikulec advocated teaching students to make video-reports in lieu of traditional research papers. Keeping the focus of the video-report on alphabetic scripting first and foremost, Mikulec insisted that “the written portion of the report should be completed first, and then visuals chosen as support material” (Mikulec, 61). Although Mikulec suggested a wide variety of visual material that could be included from still news photographs to videotaped news broadcasts, he still privileged the alphabetic medium above all else by insisting that scripting should proceed before visual composing—largely precluding the possibility that selecting and remixing images could lead students to new insights and possible revisions.

In addition to advocating the value of video-reports, Mikulec also suggested that students might compose original video-poems in which they combined their spoken reading of an original poem along with video shots of still images designed to accompany it. Once again, however, Mikulec advised that the writing of the alphabetic poem script should come first so as to guard against the “danger that they [students] may rely on the visuals to state the message” (61). By positioning visual images as simply supplemental illustration not integral to the meaning of the poem, Mikulec missed the opportunity to teach students to explore the creative possibilities of juxtaposing words and images in ways that developed complex meanings. In this way, we can see how the possibilities for video production in English were constrained by an insistent need to demonstrate how it helped students develop traditional literacy skills—a limitation that persists today in many script-driven approaches to digital video storytelling.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

As we reflect on film and video production experiments in English Journal over the years, we can see bursts of new interest in moving image production brought on by both new technological developments as well as shifting emphases on educational relevance and student-centered pedagogies. We can also see how recurring demands of austerity and back-to-basics accountability caused teachers to narrow their cinematic imaginations by putting filmmaking in service of basic skills instruction or consigning filmmaking to special elective curricula that were increasingly vulnerable to budget cuts. A few English teachers continued to publish about video production in the 1990s and interest in digital video pedagogies picked up somewhat in the 2000s with the rise of programs such as Apple iMovie and Windows Movie Maker, but discussion of moving image production never returned to the high level of enthusiasm and frequency we found in the 1930s and 1970s.

In our current moment, the availability of mobile phones equipped with high-quality video cameras greatly opens up new possibilities for moving image production in English classes, but as we seek to take advantage of the new affordances of mobile video, we should take heed of the lessons of the past. Even with widening access to camera-equipped smartphones, we must remember that access to mobile phone video editing capabilities remains unequally distributed, and that simple “bring or borrow your own tech” approaches to video pedagogy can unintentionally reproduce those inequalities. We also need to ensure that we are making space for students of all gender identites to take on directorial and technical roles in filmmaking work (Hidalogo 2017). Furthermore, while mobile video production offers great potential for activist media making, we must think carefully about how we work with students to develop critical media literacies so that they do not simply reproduce dominant capitalist, racist, sexist, and ableist rhetorics. As scholars such as Valerie Kinloch have demonstrated (2012), video production can play a key role in anti-racist critical pedagogy but only if students are given access to the means of video production in the context of a critical, race-conscious pedagogy. Finally, we take heed of Alma Reinecke’s still timely warning that English teachers risk making moving image production excruciatingly boring if we insist that it be used only to further our traditional literacy outcomes. In order to make the most of mobile video technologies in English classes, then, we need to provide space and time for students to work collaboratively with each other and their instructors in order to define and refine their own goals as media makers, while also recognizing the limitations of their own positionalities and intervening as appropriate.

In order to develop and sustain moving image production as a vital part of the English curriculum, we need to enact change not just at the level of the individual classroom, but also in deeper, more systematic ways. We need to fight for structures of educational funding in which all schools have equal access to the means of video production; at the same time, we also must fight for more capacious, portfolio-based assessment systems that enable students’ video composing to be properly valued and recognized as the crucial rhetorical work that we know it to be. We also need to fight for video production to be recognized as a crucial form of scholarship that necessitates a reimagination of current standards of evaluation in our institutions (Hidalgo 2017; kyburz 2019). We recognize that these kinds of changes may seem overly radical or utopian in our current political moment, but we also know that English teachers in the past have fought for student access to moving image production in contexts at least as vexing as our own. Let us honor the cinematic work of these teachers of the past by working hard to critically extend the powerful legacy of student film production that they have left us.