Our previous Reflections from the Trenches in the Cloud addressed instructor and student resources for teaching college writing online. Other campus roles also support online writing instruction. This week, we learn about how librarians work with online college writing and how instructors can work with librarians to support online instruction.

To Google and Beyond: Instructors and Librarians as Teaching Partners in Online Writing Classes

By Jenny Dale,

Coordinator of First-Year Programs, UNC Greensboro University Libraries

As an instruction librarian, I have been teaching information literacy skills to English composition students for nearly ten years. I have taught thousands of students in face to face courses, and my course-integrated sessions focus on the skills, strategies, and resources relevant to the research assignment at hand. The content that I cover in these sessions hasn’t changed much in the last decade, as I focus on the foundational skills necessary to access, evaluate, and ethically use information. At UNC Greensboro, research is a critical component of the College Writing curriculum, and most face-to-face sections schedule at least one course-integrated session with me or with another librarian. In my five years here, I have seen this become more and more integrated into the culture of College Writing courses, and I have seen my role as an instructional partner grow.

As UNCG has expanded its online course offerings, the number of online sections of College Writing has grown significantly. Over the past two years, I have had new opportunities to support students in these online classes, and each semester I have experimented and succeeded and failed, learning important lessons and new strategies along the way. My goal with this post is to share a few of these lessons with those of you who teach online writing classes, and to other librarians who support online writing students.

1. Become instructional partners. The most successful experiences I’ve had supporting online classes have been rooted in close collaboration with the course instructor. Having the opportunity to consult with instructors in advance on research assignments and being aware of their student learning goals makes it easier for me to effectively support an online class. Communication and collaboration are key when instructors and librarians are working together to provide research support. The easiest way that I have found to stay involved in an online course throughout the semester is to be added as an instructor or teaching assistant in the learning management system. This has made it easier for me to make announcements, post links to resources, and provide assistance via discussion boards. It also makes it easier for students to contact me directly with research questions.

2. One size does not fit all. Just as every traditional face-to-face class has its own identity, no two online classes are the same. Working together, the instructor and the librarian can develop a plan for the appropriate level of support. Each online class I’ve worked with has had unique assignments and goals, and for each I have provided different types of support. Library support for online classes spans a wide range, from simply being available for individual research consultations to a fully embedded model in which the librarian is a fully participating co-instructor. Here are a few ways that I have worked with online writing classes:

- Provided a synchronous online session in Blackboard Collaborate that walked students through an online assignment created in Google forms (http://tinyurl.com/eng101online). Students who were unable to participate synchronously completed the assignment on their own. I collected usernames (we are a Google Apps for Education Campus, which makes this easier) so that I could contact students directly if I had any comments about their strategies or topics.

- Created asynchronous video tutorials covering topics like searching library databases, evaluating websites, and citing sources. Students were encouraged to watch these videos and then complete an online library assignment similar to the one linked above.

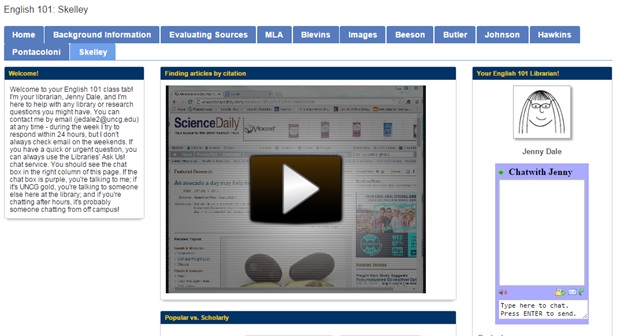

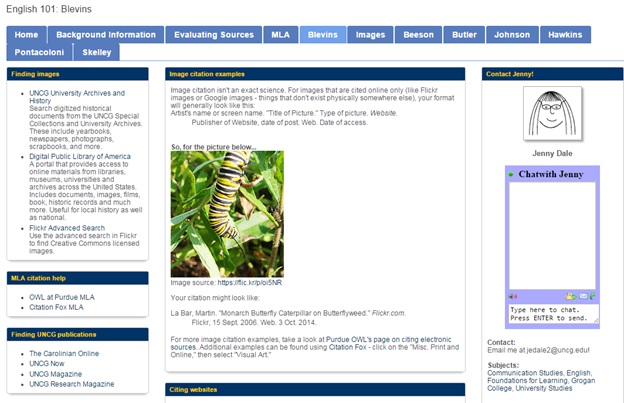

- Created customized online course guides with tutorials and images embedded (for example, http://uncg.libguides.com/eng101/skelley) and with assignment-specific resources and assistance (for example, http://uncg.libguides.com/eng101/blevins, which provides specific guidance on finding and citing images as well as advanced search tips for Google).

- Simply introduced myself, either in a short video or in a text announcement, via the learning management system early in the semester and provided email assistance to students as needed.

It is useful to develop a plan for support before the semester starts, but you also need to build in some flexibility. If the instructor notices that students are struggling with finding scholarly articles, the librarian can create or recommend resources on the fly.

3. Well-designed research assignments are critical. Good assignments are always important, but providing clear guidelines is particularly important when the assignments involve research. Project Information Literacy, an initiative of the Information School at the University of Washington, sampled research assignments from colleges and universities and found that these assignments tended to focus on mechanical requirements and provided little guidance about doing research or finding appropriate sources (Head and Eisenberg, 2-3). For online classes in particular, it is a great idea to recommend specific resources to your students – for instance, a general library database like Academic Search Complete or ProQuest Research Library. From a librarian’s perspective, I also recommend mentioning the library and the librarians as resources. Students take assignment requirements literally, and you can use this to your advantage by making clear recommendations. For research assignments, it is also critical to provide clear information about source requirements. Descriptors like “reputable,” “reliable,” and “credible” mean very little to most students, especially research novices. If you use terms like this, be sure to explain what they mean to you and give examples, like peer-reviewed journal articles, or magazine or newspaper articles. Running your assignment by the librarian you’re working with can help with this!

If you’re an online writing instructor, I would encourage you to contact your librarian! S/he can work with you to develop an appropriate and realistic plan for supporting your students’ research needs. If you’re a librarian who works with college writing or English composition classes, reach out to your online instructors! Together, we can help students combat information overload and become more informed, savvier researchers.

Work Cited

Head, Alison J., and Michael B. Eisenberg. “Assigning Inquiry: How Handouts for Research Assignments Guide Today’s College Students.” Project Information Literacy. Web. 12 July 2010. <http://projectinfolit.org/images/pdfs/pil_handout_study_finalvjuly_2010.pdf>