I want girls to be empowered and to stand up for what they believe in … to be confident in who they are and [not]to care about what others say about them. — Clarivel, 14

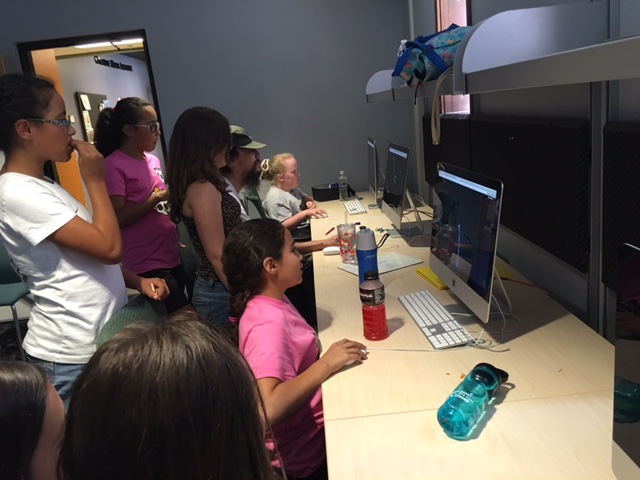

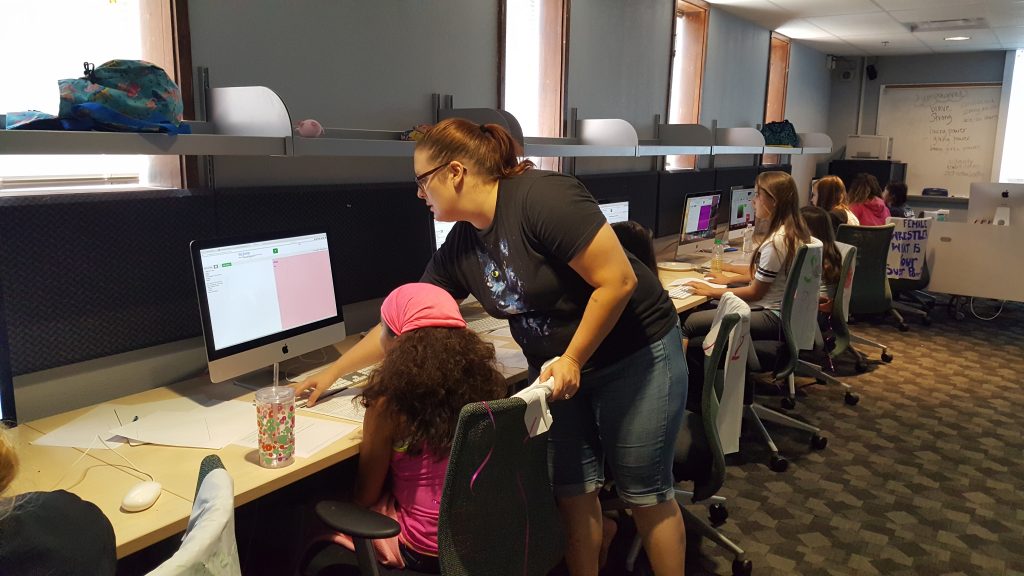

I hear them thundering down the hallway to the computer lab. Something clinks as it hits the ground, then there’s giggling. I hope it isn’t a flash drive loaded with projects. In the lab, I can feel the excitement. These girls are energetic. They’re smart. They’re creative. And they’re the next wave of technofeminists primed to make a difference in the world.

These are the girls of Girlhood Remixed Technology Camp.

Girlhood Remixed Technology Camp (GRTC) is a summer camp created to help overcome the digital divides that negatively impact many young girls by providing safe, mentoring spaces to experiment with various media and technologies. During GRTC, tween girls (roughly ages 10-14) develop the tools and language necessary to challenge harmful media portrayals and construct their own online girl identities.

Before graduating from New Mexico State University, who hosts GRTC, I served camp in several capacities: volunteer, assistant director, and director. From 2013-2016 I bore witness to girl-created zines, fairytales, podcasts, music videos, films, computer games, websites, blogs, and more. Alongside feminist coaches, we mentored—are were mentored by—more than 50 tweens as they explored, dismantled, reassembled, and remixed their girlhood identities. Here, I share how technofeminism emerged during GRTC 2016, which was generously supported through a LRNG Innovators Challenge Grant. I offer some of the girls’ work in hope that it demonstrates the importance of technofeminist mentorship and inspires others to engage in these practices in their own ways.

Technofeminism

GRTC’s approach to technofeminism draws from feminist scholars Judy Wajcman and Sharon Mazzarella. Wajcman (2004) describes technofeminism as “a mutually shaping relationship between gender and technology” (p. 7) in which “gender relations can be thought of as materialized in technology, and gendered identities and discourses as produced simultaneously with technologies” (2007, p. 293). Therefore, as Mazzarella (2010) reminds us, “the cultural and social structures in which girls live today and the role new information technologies play in their lives mutually affect each other in inseparable ways” (p. xii). In other words, technofeminists recognize that women’s relationships with technologies are fluid and negotiable. Technologies not only affect but are affected by women and girls.

Wajcman (2004) asks us to consider: “Can feminism steer a path between technophobia and technophilia?” (p. 6). At GRTC, we say yes.

Girl, Remixed

To subvert binary thinking that “tech spaces and practices [are]either dangerous or damning for girls or, conversely, saviors and gender mitigators” (Almjeld and England, 2015), GRTC helped girls move beyond basic technology skills so they could develop critical technological and digital literacies. Importantly, through hands-on media production, the girls challenged assumptions and stereotypes of women across digital spaces. Below are demonstrative girl-created projects.

A podcast challenging assumptions that girls don’t understand technology.

Hailey, Maya, Lina, and Ella wrote, performed, and edited their podcast “Apple vs Android,” which compares and contrasts technology products. Through collaborative research and productive debate, they assisted fellow campers in making more informed choices about their own technology use. This is an act of feminist mentorship. As Valentina, another camper, blogged: “[G]irls don’t have to be empowered by men, they don’t have to be scared.” The female-produced “Apple vs Android” podcast was developed start to finish without validation or opposition from men/boys. Instead, it’s girls supporting girls.

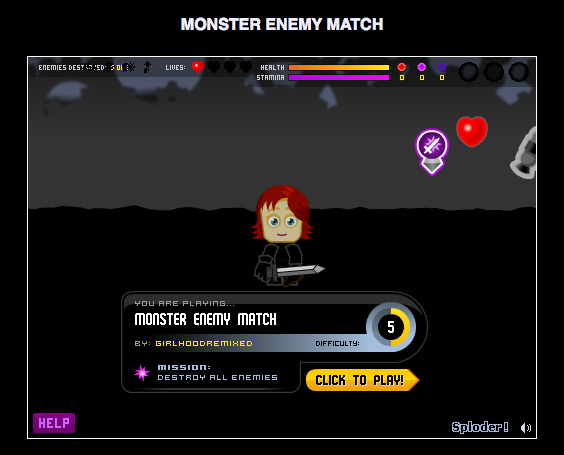

A computer game challenging sexy damsel-in-distress narratives.

Chloe created Monster Enemy Match, a side-scrolling computer game in which the player controls a warrior to defeat a series of increasingly difficult monsters. Importantly, this warrior is female. Fellow camper Clarivel had blogged: “When video games have female characters they are usually minor characters and are usually not the ‘heroes’ of the game. Most of the girl characters are damsels in distress or don’t really have a big role in the game overall.” Chloe’s character, however, isn’t feminized, sexualized, or helpless. Rather, she’s a capable leader who fights her own battles unassisted by men. She’s her own hero. Monster Enemy Match and other camper-created games are free to play on Sploder.

Moving Forward

The coaches and I watched as GRTC campers developed into technofeminists, and I also see them becoming future techno-social change agents. Kimberly Scott and Patricia Garcia (2016) describe techno-social change agents as those “who possess the skills to both use and innovate with new technologies” (p. 67) to respond to inequities and injustices “in action-oriented ways that can transform the world” (p. 74). I have no doubt our tween girls will continue to purposefully, skillfully, and reflectively use technologies to produce new digital artifacts that address complex problems such as female representations and identities in tech, digital, and media spaces.

As Clarivel shows in her final project, a camp documentary, these girls already are looking forward to how they can change the future for the better.

References

Almjeld, J., & England, J. (2015). Training technofeminists: A field guide to the art of girls’ tech camps.” Computers & Composition Online. Retrieved from http://cconlinejournal.org/fall15/almjeld_england/

Mazzarella, S. (Ed.). (2010). Girl wide web 2.0: Revisiting girls, the Internet, and the negotiation of identity. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Scott, K. A., & Garcia, P. (2016). Techno-social change agents: Fostering activist dispositions among girls of color. Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism, 15(1), pp. 65–85.

Wajcman, J. (2004). Technofeminism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wajcman, J. (2007). From women and technology to gendered technoscience. Information, Communication & Society, 10(3), pp. 287–298.