Panelists

Jill Morris, Frostburg State University

Dave Sheridan, Michigan State University

In this Saturday afternoon panel, Jill Morris (Frostburg State) and Dave Sheridan (Michigan State) engaged the audience in considering the work of more-than-just-linguistic rhetoric. Morris began the panel with her talk, “Relocated Attractions at Modern Amusement Parks: Rebuilding an Experience through Rhetoric,” in which she described her case study research on Knoebels Amusement Park in Pennsylvania. Morris used experience architecture, which she defined as “the art and science of articulating clear user journey or story through an information architecture, interaction design, and experience design that an end user navigates across products and services offered by the client or as intended by the designer,” as both a framework for understanding and a method for structuring experience in the ways that amusement parks—notably Disney parks—do.

From this perspective, she pointed out, it’s not just about being a guest in a park; it’s about participating in the storytelling. In Disney parks, for example, the experience is fully immersive, and every guest is a hero in an experience built by teams of imagineers and engineers. With this in mind, Morris sought to answer the following questions:

- How does experience architecture in these designed ecosystems recreate sensations from the past?

- Do guests appreciate the detail that goes into these recreations, and if so, are they persuaded to feel a connection with the past through them?

- If not, do they prefer rides been moved and rebuilt as Dominator was—with little or no signage noting the ride’s original location?

- And—perhaps most importantly as a writing teacher and game designer like myself—what can be learned from the persuasive environment of theme parks with historical attractions and recreated rides and applied to other forms of rhetoric?

In her case study, Morris describes Knoebels Amusement Park’s work to preserve the history of American amusement parks—not in a museum, but in reconstructing rides that haven’t been available for decades. She discussed the experience architecture work involved in recreating the Flying Turns, a wooden trough bobsled coaster, in a way that preserved the feel of the original, but that also met modern safety standards. The goal, she explained, was to both immerse park-goers in an experience of the past and to educate them about it, from the moment they step into the queue for the line. Morris also described the work of recreating the park’s 1960s-1970s-era Singing Mushrooms, for which there had been great demand on message boards. As Morris succinctly put it as she concluded, “experiences matter.”

Dave Sheridan continued this discussion of how experiences matter in his talk, “Making, Makers, and Makerspaces: The Virtual-Material Rhetorics of Digital Fabrication,” in which he presented a case of “a particular thing made in a particular makerspace,” from a larger project focused on multiliteracy centers and makerspaces in Detroit (with research drawn from interviews, observations, artifacts). After giving a description of the makerspace—a group of about twenty members who share access to a variety of tools (fabrication, musical instruments and mixing equipment, a kiln, a loom, etc.)—Sheridan gave an overview of the “cultural-rhetorical context” of Detroit, quoting a colleague from the West Coast who said, “We all thought Detroit was a fucking wasteland.”

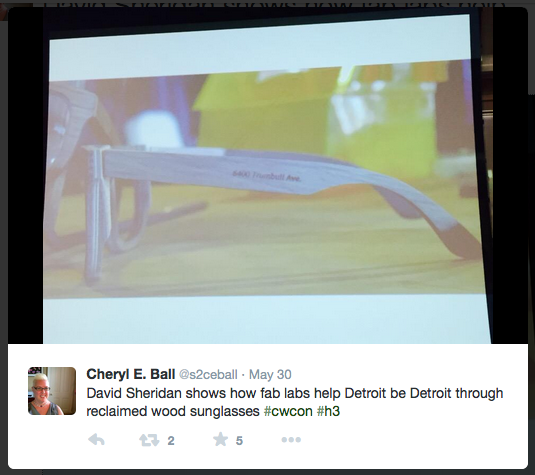

Next, Sheridan described the ways in which a watch company, Shinola, uses counternarratives of Detroit as a branding strategy. Sheridan made a case for the watches themselves as rhetoric, arguing that “these messages are built into the things that are made, which then go out into the world and generate narratives.” He also pointed out that Detroiters have mixed feelings about how Shinola (a Dallas-based company) is exploiting and appropriating Detroit. Sheridan then presented the case of a sunglasses maker (who works in the makerspace from Sheridan’s study) as another example of rhetorical objects. “Like Shinola watches, these sunglasses are made in Detroit and connected to identity of city, and engendering narratives that counter negative perceptions of Detroit,” he explained, “but the ethos is different: this maker has a long history with and commitment to Detroit.” Sheridan passed around an early prototype the maker had given him as he described how the maker taught himself Adobe Illustrator and used laser tools to cut the design, and now makes a living selling the glasses.

“To understand the argument about [the sunglasses’]rhetorical function, you have to know two things,” Sheridan said. “First, they’re made from reclaimed wood from Detroit homes slated for demolition (that is legally collected by Reclaim Detroit). Second, the laser cutter inscribes on the sunglasses the address of the home from which the wood came (people find the address online and discover it was a house they had lived in, buy pairs from him).” In conclusion, Sheridan offered the sunglasses maker’s own explanation of the rhetorical work of makerspaces and the making that happens in them: “in his view, as makerspaces populate the city, they’re creating a space for the imagination, enabling possibility and different kinds of activity. They do that through the production of things that perform rhetorical functions, engender stories.”

As the third panelist was not able to attend, the remaining time was devoted to questions and discussion. Morris’ response to a question regarding how she might use the experience architecture “template” from the amusement parks to build a writing classroom or pedagogical space brought the conversation to the question of university support and funding for models of writing instruction that engage experiential and three-dimensional rhetoric. “I would [use the template of XA in Knoebels to build my writing classroom],” she said, “if my university had state funding left.” Another audience member interested in archiving and history asked Morris to elaborate more on the park designers’ interest in preserving community, and Morris replied that fans of the park say it’s exactly right, even though pictures reveal that it’s not precisely the same. “They get the same feel,” she explained.

Questions for Sheridan centered on the relationship between making and writing and the maker movement and the university. When an audience member asked Sheridan how he would describe the relationship between making and writing, he responded, “We sacrifice analytical precisions when we make everything about writing. I prefer rhetoric. Like Bruce McComiskey says, I don’t teach writing, I teach rhetoric. ‘Composition’ has similar potential.” Another audience member, noting that makerspaces are anti-institutional by nature, asked, “wouldn’t a makerspace on a campus just be a lab?” Sheridan replied that makerspaces are not only anti-institutional; they are also about openness and allowing for play and tinkering, and not just for engineers. “A makerspace could be like a writing center that is open and available,” he pointed out. Yet another audience member followed up with the comment that makerspaces not only have a neoliberal, counterpublic identity but are also gendered spaces, and described women leaving a makerspace in Dundee, Scotland, and creating a feminist makerspace, because men were not valuing their work.

Both Morris and Sheridan push us to think about rhetoric beyond two-dimensional images and texts: they treat three-dimensional objects (park rides and sculptures, watches, and sunglasses) as rhetorical. The audience’s enthusiasm for both Morris’ and Sheridan’s research and the concerns that emerged in the discussion (funding for pedagogical spaces that engage 3D rhetoric, and the neoliberal, gendered politics of the maker movement) seem to reflect the risks and promise of this direction in our field.