The D.H. Hill Library Makerspace at North Carolina State University is the result of the growing number of university initiatives to bring DIY culture to campus, offering free-to-access workshop space and a range of tools and equipment for NCSU students, faculty, and staff. As the Communication, Rhetoric, and Digital Media (CRDM) Graduate Assistant to the NCSU Libraries, I’ve had the opportunity to assist an amazing interdisciplinary team in standing up the Hill Makerspace, cultivating a community, making technology and support more accessible to all of campus, and fostering new ways of knowing, learning, and inventing in scholarship and practice. Since the space opened its doors in June 2015, I’ve watched it grow into a site of creative exploration, play, and learning, no matter one’s disciplinary background.

Not long ago, I taught a Beginner’s 3D Design workshop at the Hill Makerspace, and at the start, I asked my attendees to introduce themselves, including discipline hailed from and reason for interest in 3D design. Among the group was a faculty member in the College of Design looking to experiment with new software to bring to his classroom, an architecture PhD student wanting to 3D model buildings described in science fiction novels, a horticulture undergrad hoping to 3D scan and modify ancient plant fossil impressions, an English MA student just there to see what’s possible…perhaps the point is clear—the participants represented a range of disciplines, career stages, and levels of experience all looking to learn and experiment with maker tools. Regardless, each participant spent their workshop time designing not simply for functionality or mass production, but for creativity and exploration. Play and tinkering, experimenting and learning new tools are at the heart of the maker movement, and are essential to bringing new worlds into being through asking different types of questions, or conversely revealing new questions inspired by the process.

It’s precisely these processes of creative material engagement that drive collaborations between Hill Makerspace staff and faculty across campus to facilitate graduate and undergraduate classes that de-center the emphasis on the traditional text for project-based work and composition. Take, for example, a Fall 2015 honors course titled “Interpretive Machines,” open to all disciplines and taught by Dr. Paul Fyfe, Associate Professor in the Department of English at NCSU. Through a critical and historical framework combined with hands-on experience in the Hill Makerspace, students were asked to re-engage “old” media in order to imagine new modes of cultural communication. While writing was still involved in the form of design journals and process statements emphasizing reflection, the final project emphasized the material—the ground-up building of some “thing” (see pp. 18-20) demonstrating critical insights from the course. Final projects included, among others, an arduino-powered surveillance book tracking both location and motion, an arduino-powered QWERTY keyboard matched to musical scales for “tone typing” that interrogated textual and aural modalities, and a conductive tape and Play-Doh keyboard embedded in an old thesaurus attached to a Makey Makey provoking consideration of algorithmically-predicted text input.

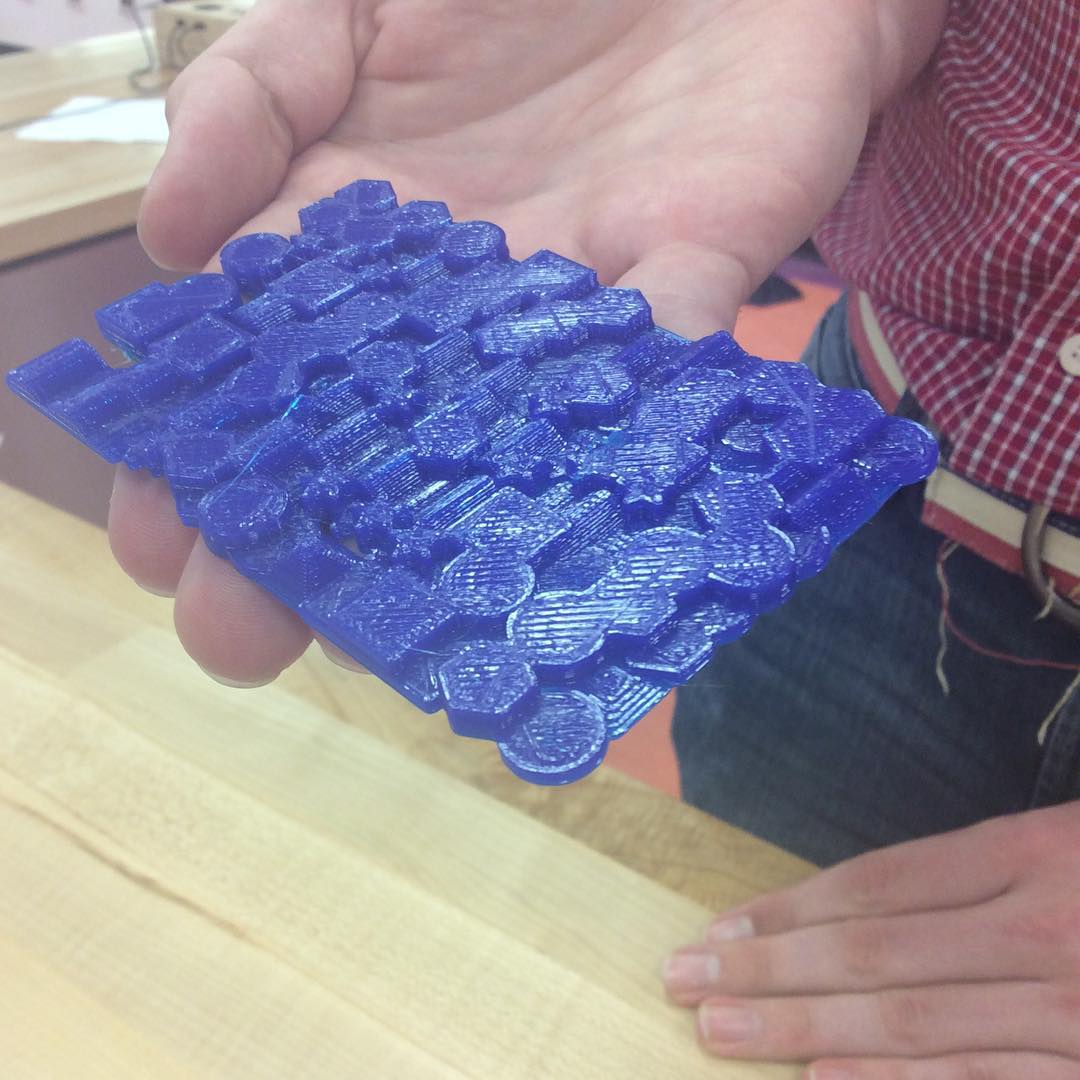

These engagements don’t follow the pursuit of mere representation in a different medium, but rather to explore and re-imagine through new media and maker techniques. Taking for example “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams, one wouldn’t necessarily want to 3D print the plums, because they’re already eaten, or even the icebox because it would just be sad without any plums…although such an idea is certainly one way to capture certain elements of the original text. However, taking it a step further, another example of re-imagined poetry emerged as a final project for a Fall 2015 graduate course in Digital Humanities: from values generated by counting phonemes in a George Herbert poem, different shapes at different heights were enmeshed in a 3D model, which was then 3D printed. Rather than a straight representation of images from the poem, this project engaged new ways of thinking about and interacting with text through unique visual and haptic sensoria.

What it comes down to is this: makerspaces, and makers, resist definition. Rejecting any method or mode of design or production, disciplinary endeavor, or cross-disciplinary exploration goes against the foundation of maker culture, an always creative, sometimes radical, and often sweeping approach to invention. While many patrons new to the D.H. Hill Library Makerspace start out by downloading and printing pre-made 3D models of novelties and trinkets from community sites like thingiverse.com, it often serves as a gateway experience to initiate ground-up building endeavors. The results of these learning experiences and products of prototyping might not be aesthetically pleasing or serve any so-called useful function, but it’s neither about form nor function. In fact, the final project doesn’t even have to “work”. Whatever the goal, as we say at the D.H. Hill Library Makerspace, failure IS an option, because it’s about the process, which challenges patrons to think with the technologies.

While my experiences seeing this process in action at the Hill Makerspace have been positive and encouraging, there are larger issues at stake deserving of a critical lens: concerns of gender and political economy, or false promises of increased marketability for humanities graduates, or limitations placed on what it means to be a digital scholar. These are big questions that don’t come packaged with simple answers, and admittedly my purpose in this post has not been to address them head on. However, my experiences as the CRDM Graduate Assistant for the D.H. Hill Library Makerspace contribute to the larger conversation regarding questions of the place and legitimacy of digital scholarship, demonstrating the desire of cross-disciplinary students, faculty, and staff to spread making across the curriculum, even in unexpected places.

So, who/what counts as digital scholars(hip)? Is one not a maker or digital humanist because s/he can’t code, or deals specifically with media art, or never produces a “working” prototype? From my own field, media studies, German media theorist Friedrich Kittler argued that coding and other practices are essential to the processes of studying and understanding media technologies. Jussi Parrikka notes Kittler’s views on tech corporations and education, considering Kittler “an active tinkerer of machines and code.” Tinkerer is an interesting choice of descriptor if we are to understand Kittler’s claim as saying one must attain expertise, but maybe instead we can read it as a willingness to experiment, and through the process better understand the technologies by digging deeper, leading to new forms of knowledge. Making as a form of epistemology, and building, as discussed by Stephen Ramsay and Geoffrey Rockwell, as a form of methodology, discourse, and scholarship. For me, for the students, faculty, and staff visiting the makerspace to develop their projects and find solutions to problems, experiencing making in action seems to relieve any anxieties about the legitimacy of these endeavors or their rightful place across the curriculum.

This is my starting point to tackle the larger questions of gender, politics, outside validation, and the power relations shifting, ebbing, and flowing in maker culture and makerspaces as they have in other forms of hobbyism. In the meantime, by bringing the classroom to the makerspace, by encouraging various forms of engagement with maker tools and tech as modes of composition, together we make beautiful music…or rather, maybe we can write a program that generates line and/or color elements based on the tonal ranges of beautiful music that we can then etch in the laser cutter to demonstrate how…okay, you get the idea.