Title: ‘Can we block these political thingys? I just want to get f*cking recipes:’ Women, rhetoric, and politics on Pinterest

Author(s): Katherine DeLuca

Publication: Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy

Publication date: 2015

Experience here/Website: http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/19.3/topoi/deluca/index.html

Title: Super Mom in a Box

Author(s): Lindsey Harding

Publication: Harlot

Publication date: 2014

Experience here/Website: http://harlotofthearts.org/index.php/harlot/article/view/197/155

Title: Queer-the-tech: Genderfucking and anti-consumer activism in social media

Author(s): Matthew A. Vetter

Publication: Harlot

Publication date: 2014

Experience here/Website: http://harlotofthearts.org/index.php/harlot/article/view/195/148

For several years now I have been a sporadic Pinterest user. When I am seeking new recipes to try, craft ideas, and money-saving tips, Pinterest is my “go to” site. However, my interest never went much deeper than that. That is, until I encountered Katherine DeLuca’s article “’Can we block these political thingys? I just want to get f*cking recipes:’ Women, rhetoric, and politics on Pinterest” published in Kairos. Here DeLuca began to explore the intersections of gender, identity, and Pinterest. I hadn’t really taken the time to think about assumptions of the predominantly female user-base and their interests, and upon reading DeLuca’s article I immediately became critical of my own experiences and practices. Was I the stereotypical woman Pinterest panders to? As a self-identified feminist who isn’t very good at cooking or very crafty (that’s why I go to Pinterest!) I don’t tend to think of myself as such, but my practices on the site tended to reflect something else. From here, I delved into two other webtexts (both composed by former DRC fellows!) that similarly addressed the intersections of gender, identity, and Pinterest in their own unique ways: Matthew Vetter’s “Queer-the-tech: Genderfucking and anti-consumer activism in social media” and Lindsey Harding’s “Super Mom in a Box” (both published in Harlot).

DeLuca’s article considered the civic engagement, composing, and cyberfeminist practices that occur on Pinterest. In particular, the author found that Pinterest isn’t merely a social media site to simply write off because it’s just women sharing recipes. Instead, her research demonstrated women use the site to share recipes, crafts, and the like, but it also demonstrated noteworthy composing practices. When political pins became involved, there were extensive discussions and debates on whether or not there is a place for politics on Pinterest, and it also sparked discussions on women’s rights and women’s activism. Although the user base shaped Pinterest into what it became normalized for (a woman’s space for sharing crafts and recipes, broadly), there is also room to challenge those norms through politics, cyberfeminism, women’s rights, and so on that effectively challenge Pinterest norms. The webtext design itself challenges the normalized Pinterest experience as DeLuca imitated some design aspects that would be familiar to Pinterest users.

In particular, DeLuca included navigation buttons that imitate the design of a Pinterest Board, and each one includes photos that connect back to the major topics addressed in her webtext: politics, cyberfeminism, and women’s rights. After clicking one of these initial boards, DeLuca takes the design further by then inviting readers to click individual pins on the board to further navigate the webtext. DeLuca’s design is the most intricate of these three webtexts since the images of Pinterest boards and pins serve a navigational purpose in addition to serving as examples.

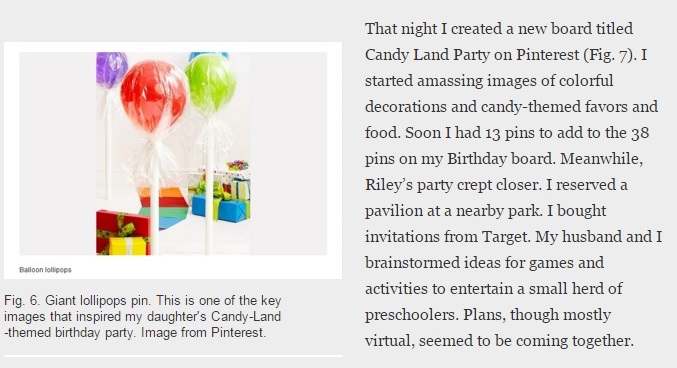

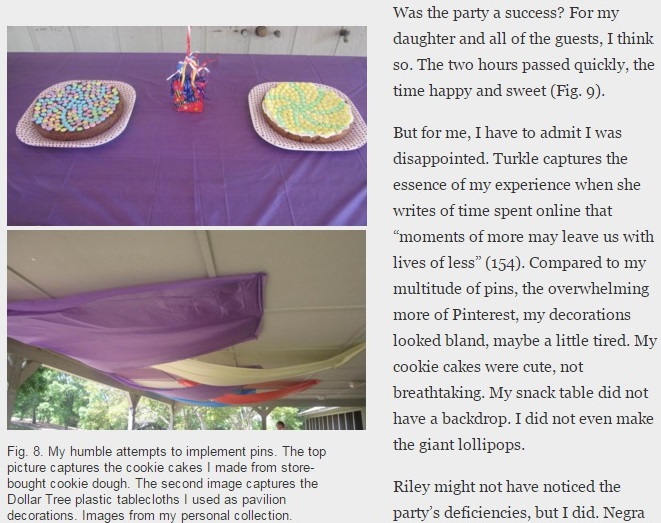

Harding’s article focused on how users can fall into this false sense of accomplishment through pinning. Through amassing over 1000 pins, Harding felt like she had become “super mom” because she had recipes, party planning, crafts, family activities, and so much more ready to be used at a moment’s notice. However, Harding began to realize that this was just an illusion for her, as it likely is for many as well: “That is, I came to feel like a crafty mom by pinning DIY projects to my Craft Ideas board even though I didn’t even own a glue gun.” The reality is, when trying to bake the perfect cake found on Pinterest or plan the perfect party, a person’s own money, resources, and craft skills can only go so far, and the end result is feeling underwhelmed because what was created doesn’t match the picture-perfect rendition seen in the pins.

Harding portrayed these “picture perfect” pins in comparison to her own party photos throughout the webtext to further highlight how, visually, users’ creations often are not “picture perfect” creations. Harding described this as Pinterest putting her in the “confident, creative mother” box, which exemplifies exactly what Vetter’s and DeLuca’s focus on queer and cyberfeminism in Pinterest, respectively, aimed to critique. Through incorporating a combination of pins and some of her own personal photos, she gives readers a different way of seeing Pinterest creations–it may not look exactly like what the user pinned, but that does not mean the creation was unsuccessful. Instead, Harding explained the joy she has found in the unplanned moments–and that, quite frankly, young children don’t care about centerpieces at a birthday party.

Vetter’s article focused on how we can “queer the tech,” which he defines as realizing the cultures-of-use around technology and appropriating it to give voice to those silenced or marginalized in the technology. Vetter did a sample of this work using the site Pinterest, a technology that generally upholds heteronormative values and beliefs, but here he “queer[ed]the tech” by creating new pins from outside source material (rather than merely repinned posts, which tends to be most frequently done) that challenged heteronormative values. For example, he created pins about queer, trans, and gay lifestyles and billboards, signs, and images advocating queer lifestyles and/or ideologies that resist normalized expression of gender and sexuality. Examples of these pins appear through the webtext as images to further highlight his argument, and he included a link his “queering Pinterest” board in the abstract of the webtext for readers who wish to explore queering Pinterest beyond the scope of the webtext. Like Harding, Vetter used images in his webtext to provide further evidence of of how users can queer the tech in Pinterest. One of the most compelling aspects of Vetter’s webtext comes in the form of hyperlinks. He linked to his sources, but he also linked to Pinterest. Vetter invited readers to queer other technologies, and to participate in queering Pinterest, in an effort to promote activist work via social media.

Vetter used the technology at hand to strengthen his invitation by including a hyperlinked image at the end of the article asking readers to “Join Pinterest.” Even if his call for participation did not engage all readers, by visiting his companion “queering Pinterest” board, it is clear his efforts have been successful to some degree with one pin being repinned approximately 7,200 times and being liked approximately 2,800 times. Although these numbers may be a bit small by Pinterest’s standards where pins can easily go over 10,000 and even 100,000 repins, it does demonstrate success, at least insofar as the queer content posted here being further circulated.

What I love about all three of these webtexts is that readers are positioned in a way to become active creators of their own content and social media use. Indirectly, Harding and DeLuca challenges readers to step back and realize the gendered aspect of Pinterest that may not have been prominent otherwise. I, for one, didn’t even know Pinterest featured politics, women’s rights, and activism, but I have since sought out these pins specifically to better engage with these conversations that, for me, are compelling and personal. Harding, too, encourages readers to take a hard look at social media practices. Are pins an escape from reality? A space to create the ideal identity and representation of self that is unrealistic given one’s own lifestyle, experiences, and resources? Vetter, though, makes a much more explicit invitation. He started to queer the tech with a Pinterest board, and he invites other readers to continue doing this work to push this project to new lengths.

Furthermore, all three of these webtexts challenge readers to think about what is normalized through various social media sites–whether it be Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or countless others–and how users may be inadvertently upholding unrealistic, and potentially harmful, normalized standards of participation and engagement. As users of these and other technologies, users should work to become critical users to bring awareness and criticisms to the technologies that make it all too easy to just embrace the normative methods of participation rather than adopt a critical stance.