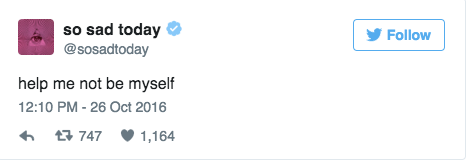

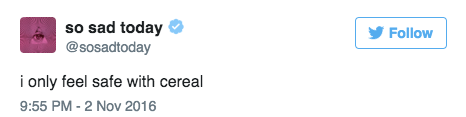

When my Twitter-less friend recognized Melissa Broder’s recent personal essay collection, So Sad Today, on my bookcase I began to understand the pervasiveness of Broder’s influence. However, it wasn’t until after I enrolled in a graduate course concerning the digital humanities, that I began my reconsideration of digital publishing and my recognition of Broder as a participant in these digital age practices. Broder’s digital branding of her aesthetic on Twitter preceding her publication was ingenious because it spoke to the multi-modal manner in which we as scholars, educators, authors, and digital humanists consume information. Anonymously creating her Twitter account, @sosadtoday, in 2012, Broder’s philosophical musings juxtaposed various topics ranging from sexuality to mortality, the mundane with the existential, in order to inject each tweet with gravitas matched with dismissive humor. Broder used Twitter as a tool to archive her work for posterity, in which the ideas preserved on the platform were incorporated into the themes, or even titles, of her personal essays, including “Never Getting Over the Fantasy of You Is Going Okay” (139), “The Terror in My Heart Says Hi” (127), “Help Me Not Be a Human Being” (27), and “Hello 911, I Can’t Stop Time” (113).

Twitter can be an artistic platform for digital publishing. Broder seems to use the convention of the concise, 140-character tweet as an incubator for her more grandiose ideas, on which she elaborates in her essays. In addition, Broder utilizes the popular social media platform in a novel manner: to preserve her anonymity.

The anonymous aspect of the internet-personality she cultivated is a particularly intriguing aspect of her philosophy. It was not until her Rolling Stone interview in May 2015, while promoting the highly-anticipated release of So Sad Today, that she identified herself as the poet, Melissa Broder, and claimed her formerly-anonymous Twitter handle. In this way, her style of digital publishing is turning the established paradigm on its head and further blurring the definition of what exactly constitutes authorship and publishing in the digital age. As an author, poet, and essayist, Broder’s fosters a distinctive style of confessional prose, published in a contemporary, digital format, from a (formerly) anonymous point of view.

In the essay “I Don’t Feel Bad About My Neck” (83), Broder turns Nora Ephron’s satirical August 2003 essay inside out, most obviously by inserting “Don’t” in to the title, but more subtly in subject matter and tone by replacing conventional notions of vanity with jarring sexuality in the ubiquitous obsession about aging, in lines such as “I feel bad that my vagina used to be more pink” (85), “I feel bad that I don’t have a dick” (87), for example. Her rationale turns to assorted, abstract anxieties including maternal fantasies, “I feel bad that sometimes I wish to just be struck pregnant” (84), and gripes with systemic racism, “I feel bad that as a white girl I can go shopping in certain store and won’t be eyed, bothered, humiliated, kicked out, unlawfully arrested, or shot, and that the same is true for me of pretty much all places, institutions, and public parks. That’s not true for all human beings” (90). However, what is most revealing are the final two lines that perhaps encapsulate an essential truth of Broder’s collection, if there is one to be identified, which is her sense of indelible humility. Preceded by a sentence in which she concedes her “struggle…is nothing compared to other people’s struggles”, “yet”, she acknowledges, “it still hurts”, she admits:

“I feel bad about this essay.

I feel bad about this book.”

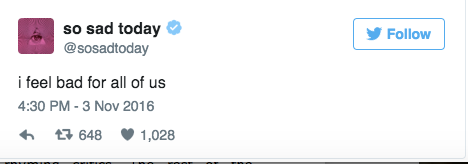

Perhaps, these final sentiments function as veiled responses to criticisms that her aesthetic glamorizes mental illness, a topic which she is vocal throughout her essay collection, in her poetry, on her @sosadtoday Twitter, as well as on her personal Twitter, and in interviews (“I see myself trying to patch a hole inside me that cannot be patched by anything external”, So Sad Today, “I Took the Internet Addiction Quiz and I Won”, 73).

Broder manages to approach these complex topics with humility and unrelenting honesty, that goes beyond cringe-worthy, and she implores for the reader’s attention as well as emotional and intellectual engagement to comprehend, digest, and respond to them. As Carlin Romano distinguishes “reading a book … requires concentration, endurance, the ability to disconnect from other connections”, as opposed to digital engagement of social media. Therefore, Broder’s use of Twitter increases the accessibility of the art she publishes simply because the platform in which it is published is interactive, and better yet, practically live. Followers can engage with Broder in the comment’s section, favorite, retweet, interact and react to her ideas, concepts, and feelings. Arguably, this advent allows “interested readers feel engaged and involved with the publishing process of a title, [and therefore]they are more likely to spread their excitement to other users” (Criswell, Canty). The reality of her parlaying an anonymous, existential internet-personality on a condensed social media platform into a published collection of personal essays is a testament to the digital culture we inhabit, and the evolving possibilities for the circulation of art on platforms such as Twitter in the future.

Works Cited

Criswell, Jamie, and Nick Canty. “Deconstructing Social Media: An Analysis Of Twitter And Facebook Use In The Publishing Industry.” Publishing Research Quarterly 30.4 (2014): 352-376. Academic Search Premier. Web. 11 Nov. 2016.

Romano, Carlin. “Will the Book Survive Generation Text?.” Chronicle of Higher Education 03 Sept. 2010: B4+. Academic Search Premier. Web. 11 Nov. 2016.