Presenters:

Christina V Cedillo, University of Houston-Clear Lake

Ana Milena Ribero, Oregon State University

Sonia C. Arellano, University of Arizona

Review:

Christina V Cedillo

As part of the design of this maker session, participants were encouraged to visit the stations that the facilitators had set up in their assigned room. I decided to go to Christina Cedillo’s first, since it was the first table I encountered as I walked in. Some of the fellow participants in my group were Angela Hass, Elise Versoza Hurley, Matthew Cox and Marilee Brooks-Gillies, among others. Christina Cedillo opened her session by stating the title, “Intersections of Immigration and Identity,” and asking, “in the classroom, how are we doing this?” To provide some context, she mentioned how in Houston, medics were calling Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which became even more complicated when Hurricane Harvey hit Houston. She called it a “perfect storm of people willing to die so that they don’t get deported.”

To follow up, Christina Cedillo mentioned that what she wanted us to further think through the modalities that would give us different entry points to communicate immigration issues. As the co-editor of the Journal of Multimodal Rhetorics, Cedillo urged participants to consider how multimodal choices could result in moments of less resistance, or in different kinds of resistance, from students grappling to understand the intersections of immigration and identity. An example she provided reconfiguring the actual classroom space and how that would lead to beneficial exchange. Matthew Cox mentioned how when people aren’t comfortable enough speaking in a large space, arranging the space of discussion into small groups affords moments of talking about uncomfortable topics. Marilee Brooks-Gillies followed up by saying how students having particular roles in small groups—like one person will take notes, while others convey ideas, or work alone—gives them more agency and comfort-ability to participate.

Angela Hass also emphasized the importance of giving students opportunities to hash things out using the example of how disability-based identities intersect with undocumented status. “How can we unpack these in every day rhetorical efforts?” she asked. For her, at the graduate level it is already there: “we talk about rhetorics of normalcy as an introduction to technical communication… We talk about visas, we talk about treaties,” which is all really important emancipatory work!

Christina Cedillo closed the session by pointing to the intersections of race and disability, specifically noting the importance of having statistics about all kinds of medical resources and their differential availability. She also provided a handout with the resources she uses to address all of these intersections in her classes.

Ana Milena Ribero

The session focused on Ana Milena Ribero’s developing “Academic Activism Methodology.” To start, she explained how the recent presidential election was the moment that she decided she wanted to act more to protect this vulnerable population. But, she then asked the participants, “What is an academic activist? What are the risks of academic activism? Not just at the practical level (promotion) but also the practical level of (un)belonging.” She proposed an Academic Activism Methodology, which at this point is aspirational.

She explained that she was influenced by Valeria Pecorelli’s wanting to do this work in her career—to involve social change in research practice as a methodology. Ribero seeks to counter the myth of “If I’m writing about it, I’m not being active.” For her, writing in academia is doing the activist work, especially when it forwards social change, and she thinks a collage methodology is the best way to achieve this goal. A collage methodology, as Ribero describes is putting together three different activist-oriented methodologies. What follows are a few of the main characteristics of a collage methodology and how Ribero sees each operating:

- The first methodology—Eve Tuck’s desire-based research as an anti-dote to damage centered research—focuses on how oppression can singularly define a community. This methodology is useful because documented oppression obscures the historical context for that oppression, so desire-based research allows for further understanding of complexity, contradiction and self-determination to live lives.

- The second methodology, feminist action research, centers on the experience of minoritized populations. Feminist action research is a bottom-up practice, research, and theory that works toward social change. It thrives on research reflexivity or how researchers may use their power and position to diffuse power dynamics.

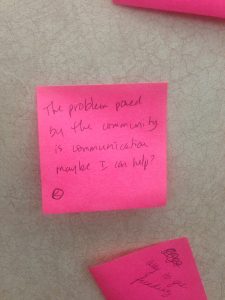

- The final methodology in Ribero’s college methodology, direct-action organizing, is the process of leading social movements toward tangible change. Direct action organizing is activist research that addresses a problem posed by the community. It is a kind of research that addresses people, not texts. Although in this research, multimodal texts may invoke inductive reasoning through an impasse based on what the multimodal text is showing.

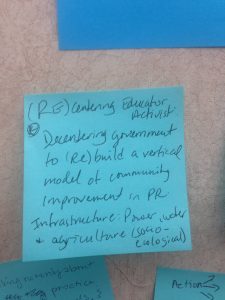

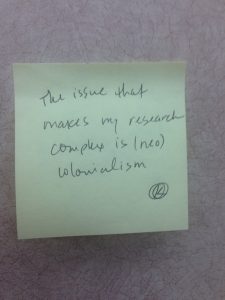

Ribero wonders if this collage of methodologies may address identifiable improvements and asks: “How are social movement rhetorics creating a campaign/rhetorical argument for the rights of undocumented people?” By taking up this kind of methodology, she hopes people may become more aware of their collective power, while avoiding a deficit model that looks for something that is not there. The research, then, would reflect the knowledge of communities engaging in social movement rhetoric as opposed to an academic imposed critique. As part of the maker session, Ribero closed by asking how this kind of collage methodology could be useful for a current or future project. I took some notes using the sticky notes provided and here is what I wrote:

Sonia Arellano

“Possibilities of activism through quilting as method” was the last maker session I attended. In this session, Sonia Arellano explained how her dissertation project was inspired by quilts that mapped the deaths of migrants in their journeys. After giving credit to the activists that inspired her work, she instructed us to get started on our own quilting with a mini-quilt project that related to our own activism or research. For her, quilting and activism are the same.

Quilting as a method was her way to put together her research and activism whereas quilting as just a side hobby wasn’t sustainable in her dissertation writing process. As a method, quilting offered a way to demonstrate research in terms of a tactile text.

Marilee Brooks-Gillies noted that she brings in different making practices into her classroom, and students really get baffled at the fact that they are able to make a thing. A participant then noted that she really just wanted to tinker. This statement reminded me of a paper I delivered in the last Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference, where the theme was women’s ways of making. My work then focused on the importance of remembering the ways in which mundillo (a particular Puerto Rican lace form) was used by the United States tourist industry to celebrate Puerto Rican women’s needlework while maintaining the low socioeconomic positions of these women. I recalled this paper out loud to suggest that while I see the value of tinkering, and making, perhaps to help our students become comfortable with the messiness of composition, it is also important to recall the fraught histories of making for third world and other colonized peoples.

Brooks-Gillies admitted she has noticed that scholars who study tinkering are mostly white and male, while making has been around forever. Arellano followed up to note how quilting has a long history connected to those who know how to sew, and that those histories are really diverse. A few examples she brought up were African American and Native American communities, for whom sewing has been a mode of honoring survival and story-telling.

After this moment, Matthew Cox shared how his mother is an avid hobbyist who always mentioned wanting to sew a dress for the person he was marrying. Given Cox’s queer identity, and the fact that he was marrying a man, his mother did not sew a dress. Instead, she made him a quilt. Arellano then reiterated how quilting brings different community identities, which can provide a critical application to our composition classes.

Ultimately, we all took our mini-quilts home, which provided a tangible take-away to go with the rich discussion on activism and composition research.