What are we to make of the “self” captured in a “selfie”? If one is both author and subject of an image, we might claim a compelling authenticity. But like Donna Haraway’s “cyborg,” the “self” captured in a selfie is subject to replication, participating in mutable, sometimes strategic, subjectivities. Both atoms and bits construct our reality.

Extending Haraway’s articulation of the “leaky distinction” between animal and machine, this post considers the intersections of embodiment, agency, and digital modes of being, by way of the selfie—in particular, selfies’ re/production of malleable digital bodies. I theorize malleability, or the capability of being stretched, bent, or adapted, via the smartphone app “SkinneePix.” The app foregrounds the instantaneity of digital photographs and selfies’ social media component to make a potent claim on the in/visible body image. While the app was discontinued in 2016, it remains a hallmark of so-called “beauty apps” that offer users the opportunity to (usually covertly) modify their selfies before sharing them on social media. SkinneePix is particularly interesting in its focus on artful face “slimming” and its promise of real, more accurate representations of its subjects.

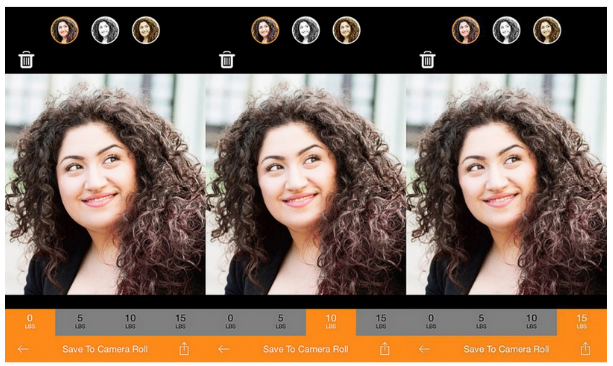

The SkinneePix app, dubbed a “fun” way to make “pictures thinner,” digitally thins a subject’s face in “two quick clicks on your phone” to balance out the 15 lbs. “the camera adds.” Created in 2014 by journalists-turned-entrepreneurs Robin J. Phillips and Sue Green, the app gives users the option of trimming 5, 10, or 15 lbs off their headshots. In an interview with the LA Times, Green explained she “sees SkinneePix as a playful app that can be used among friends for entertainment. ‘It’s a fun app, you play with your friends, and it’s just like, holy geez, look at that!’”

But SkinneePix eschews dysmorphic photo modification in favor of something far subtler. Indeed, users are to feel both empowered and even clever for their image manipulations, despite claims to the “real.” Green and Phillips frequently remark that a woman’s body image is a “personal issue,” deploying a Q&A centered on rhetorics of self-confidence, freedom, and choice. They frame any concerns about body image as coming from “outsiders” who threaten people’s ability to self-determine, maintaining that “it’s [app users’]decision, and theirs only, not some outsider who is telling them how to look.” They are “supportive of free choice, for everyone…” and reject any claim that the app reinforces the desirability of thinner bodies (hardly surprising given the app’s mixed reception): “We did not set out on this project to start a conversation about body image,” they explain. “What we have done is given a person the option of how they want themselves to look to their friends.”

“Getting Healthy With My Selfie”

Beyond self-representation on social media, the app makes crucial claims on self-betterment. We are told that Green has taken the “SkinneePix Challenge,” described in her post “Getting Healthy With My Selfie.” Green writes: “[SkinneePix] allows me to think about losing the weight in small, attainable amounts, and it allows me to see my progress, a few pounds at a time.” The adjusted selfie acts upon her in some fashion, inspiring and motivating her to become not thinner, she clarifies, but healthier. And as the catchy title, “Getting Healthy with my Selfie,” hints, she and her selfie are in this together.

The SkinneePix selfie ultimately becomes a highly personal way of feeling, not simply an image reinforcing a particular look. Green ends her revelatory post with, “I don’t care what society thinks about how I should look. […] I only care about how I feel,” thus displacing the image’s centrality in favor of a modified inner self. In this process of self-betterment through weight loss, the selfie becomes an ally—a twin—extending [her]self into an imagined future. It is both more realistic, revealing how one “really looks,” and aspirational, maintaining an ambitious authenticity that straddles both present and future.

Pixels Are Pounds

In the process of image alteration, SkinneePix reinforces bodies and body images as trimmable, even in-flux. Selfie-modification is corporeal, as the app doesn’t just alter a subject’s width, it alters weight. Digital bodies are real bodies, and pixels are pounds. The camera, like food, is capable of adding to one’s mass, and the app has the technological chops to take this mass away. Yet such changes are carefully managed, much like the faces being manipulated. The 5/10/15 lb framework delimits one’s digital weight loss. Ultimately, making “pictures thinner” becomes interchangeable with making selves thinner, and the alterability of the photograph is layered onto notions of a fluid, changeable digital body. The digital and physical self simultaneously blur together and interact, a cyborgian self that thins, stretches, and morphs.

Unlike the cyborg who has already been augmented, or changed, the malleable body lives in a space of imagining, of aspiration. Viewers must recognize the selfie as both a captured digital version and, for the app user, a possible future self. Part and parcel of this malleable self, then, the SkinneePix selfie has its own claim to the real. In Green’s words:

The SkinneePix app photos help me see that […] I just have to get to a point where I feel healthier. […]And when I am having a bad day or bad moment, I will open my phone to that picture and look at my smiling face. There are no packaged meals, or shakes or anything like that. It is ‘me and my Selfie.’ I walk with my phone in one hand with my Selfie pic from my SkinneePix app smiling up at me.

Works Cited

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century.” Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge, 1990, pp. 149–181.

“SkinneePix.” Pretty Smart Women, prettysmartwomen.com/skinneepix. Accessed 14 Nov. 2017.