Content warning: References to sexual assault and online harassment

As we consider digital rhetoric’s futures, I want to think about ways that we can study digital networks, and communities and interactions on digital networks, better. And by better, I mean, more thoroughly, more descriptively, more rigorously. How can we better examine digital writers and the traces that they leave online? To start that conversation, I need to tell you a story, one I haven’t been able to get out of my head.

The Incident

This is a story about Andrea Noel, a journalist based in Mexico. I first heard her tell her story on the technology podcast Reply All, a show produced by Gimlet Media and hosted by PJ Vogt and Alex Goldman that tells human stories about technology and tech culture. While I first encountered Noel’s story in podcast form, you can also read her account on the Daily Beast, here.

Noel’s story began with what she calls “The Incident” – on a walk through her neighborhood in Mexico City, a man came up behind her, lifted up her skirt, pulled down her underwear, and then ran away. Immediately after the assault, Noel noticed a surveillance camera on the street that captured the entire incident. She tracked down the footage, which showed a blurry close up of the man’s face as he ran away. Noel decided to share the footage of her own assault on Twitter and asked her followers for help in identifying the man in the video.

Noel’s tweet inspired an outpouring of support, with others sharing their own stories of assault and harassment, using the hashtag #MiPrimerAcoso (MyFirstAssault). Noel’s story was also one of several stories around that time that led to one of the largest demonstrations in Mexico against sexual violence. But it also brought Noel harassment and death threats, which got worse when Twitter users accused Andoni Echave, an Internet personality with a television show called Master Trolls, where he played pranks on unsuspecting pedestrians and bystanders. Echave’s show was cancelled, and the online conversation around the assault footage was described by Vogt “like the Kennedy assassination film,” as each side argued over whether it was Echave in the video. Noel was also harassed on Twitter by a coordinated troll gang; no matter how many times she reported the account of the ringleader, who went by the name “Pasta Prophet,” and his followers, they were soon back on the site with new accounts and 10,000 immediate followers. He would retweet her messages for his followers to attack, and even tweeted out her real-time location. After being targeted in her own home, Noel moved and then finally left the country.

She was forced to return a few months later when the Mexico City police found additional footage of the attack, which required her to have a preliminary hearing in front of a judge, where she has to say publicly that she believed Echave to be the offender. While she is flying to Mexico City, though, Echave got access to the footage and shared it online. The additional footage showed an attacker that looked nothing like Echave. Noel landed in Mexico City not only as a woman who accused a television personality of assault, but one who did so falsely. The police stopped investigating her case entirely, and she left the country again.

If we ended the story here, this might be an Internet story about harassment and trolling online. As digital rhetoricians and researchers, we might collect and analyze tweets using the #MiPrimerAcoso hashtag, or we might examine both these tweets and those of the Twitter mob that attacked Noel, drawing some conclusions about the promises and limits of online activism, armchair Internet detectives, and the nature of Twitter trolls and harassment.

But Noel wanted to know more about the coordinated harassment effort against her, and she went digging. She tracked down “Pasta Prophet,” learned his real name, and then contacted him for an interview. After interviews with him and a number of his employees, Noel learned that the harassment that had consumed most of her life for the past year was only a small piece of a much larger plan. “Pasta Prophet” was an online operative hired by the political party PRI to get their candidate, Enrique Pena Nieto, elected to the presidency in Mexico. Pasta used his hired troll army to find and promote other stories and hashtags in order to manipulate trending topics in Mexico and suppress negative stories about their candidate, who did win the Presidency. In the Reply All podcast interview, Noel described the strategy as filling the Internet with white noise to drown out negative stories about Nieto, and she was the white noise. All of the harassment, the death threats, the stress and anguish, wasn’t really about her. It was a game to manipulate the national online conversation and to suppress stories unfavorable to this particular candidate.

Researching Comprised Platforms

This story might feel familiar, and it brings to mind similar questions to those discussed in congressional hearings surrounding the U.S. 2016 Presidential election, the Russian disinformation campaign, and the responsibility of social media companies in policing harassment and fake accounts. But it also raises questions for rhetoric scholars in studying social media platforms. There is a good deal of research in our field that analyzes online discourse and communities through hashtag searches, Twitter scraping, and discourse analysis. In this case, though, these methods would capture what was happening on the surface, but it would not come close to reaching the underlying story.

Leigh Gruwell (2018) reminds us that in studying social media platforms, we have to consider that this online discourse does not just appear in a neutral space but is also shaped by the policies and ideologies of the platforms themselves. I would extend her argument and offer that we have to consider that the discourse we study online might be weaponized for other aims. Michael Trice and Liza Potts (2018), for example, have chronicled the ways that GamerGate activists disrupted and subverted the media platforms they engaged in for their own aims. In conducting rhetorical analyses of online discourse, of course, we can never really know the motives of the individuals involved. But their rhetorical aims might be antithetical to the ones we see on the surface. Heightened conversation around a particular hashtag, for example, might not reflect how many people care about and are engaged in discussing a particular topic on a social media platform, but instead simply indicate that the hashtag has been weaponized for other aims. How much can we take trending topics and social media conversations at face value? Now that we know these spaces are used to spread disinformation and create artificial echo chambers, how do we proceed?

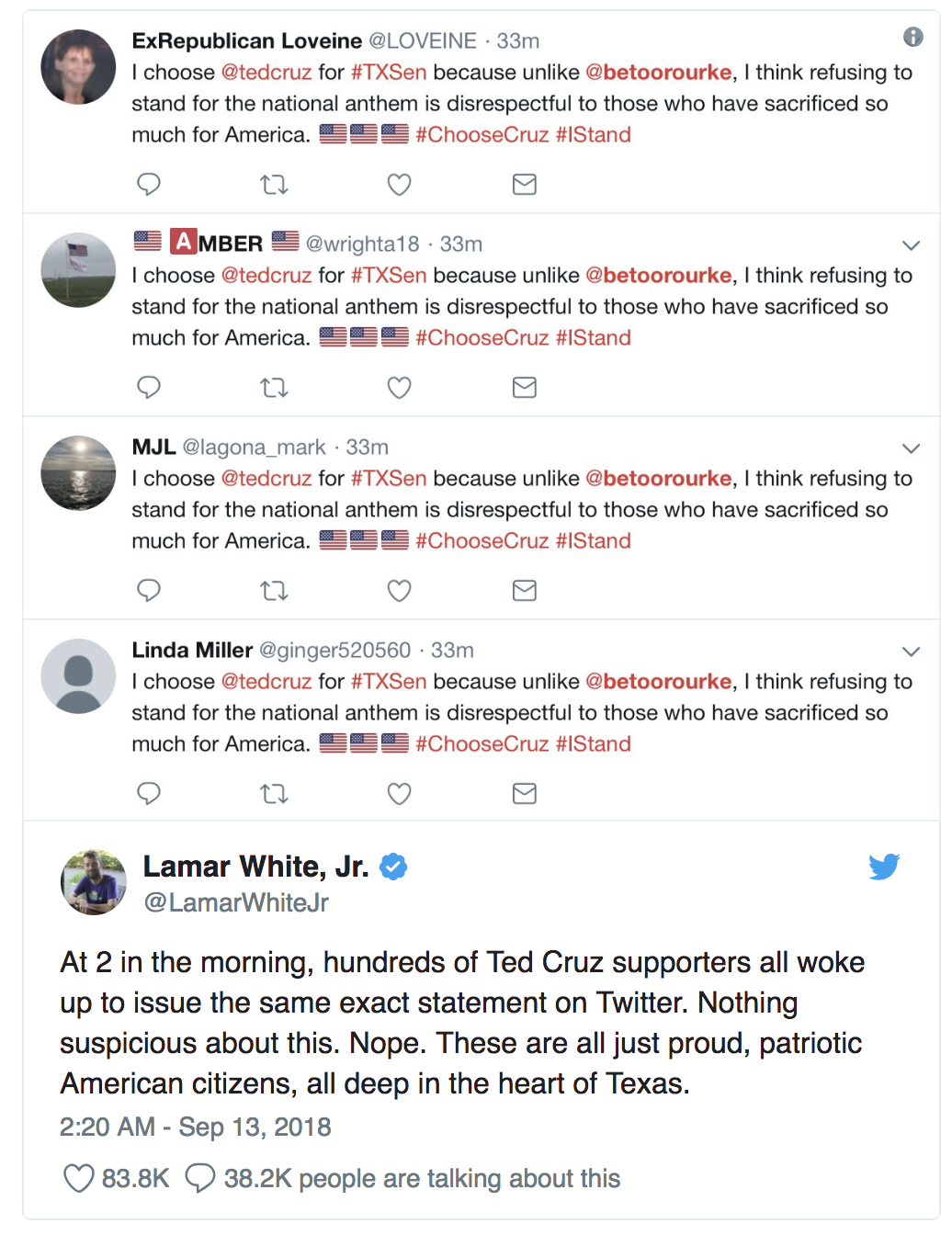

We need to watch for and pay attention to signs like the image to the left, where discrete accounts indicate their support for a particular political candidate, but most likely are the work of one individual, perhaps collaborating with others to influence conversations about that candidate online.

We need to watch for and pay attention to signs like the image to the left, where discrete accounts indicate their support for a particular political candidate, but most likely are the work of one individual, perhaps collaborating with others to influence conversations about that candidate online.

I don’t have definitive solutions to these issues, but I present them instead as problems to consider and work through. I do contend, though, that we need to rethink using social media platforms as representative of views or discourse on specific topics. I also recommend that when researchers collect social media data for analysis, they consider removing duplicate messages that appear over and over from different users, and evaluate potential fake accounts for removal from datasets. Ultimately, my own solutions involve relying on qualitative research methods and interviews to further investigate literate activity beyond and behind the screen. Interviewing individuals, as Noel herself did, can provide a perspective beyond the digital record that remains on the platform. But I also urge us to continue to evolve our digital research methodologies to address these concerns.

References

Gruwell, L. (2018). Constructing research, constructing the platform: Algorithms and the rhetoricity of social media research. Present Tense, 6(3). Retrieved from https://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/constructing-research-constructing-the-platform-algorithms-and-the-rhetoricity-of-social-media-research/

Noel, Andrea (2017, March 18). A viral sex crime saga of perverts, pranksters, and prosecutors. The Daily Beast. Retrieved from https://www.thedailybeast.com/a-viral-sex-crime-saga-of-perverts-pranksters-and-prosecutors?ref=author

Pinnamaneni, Sruthi; Bennin, Phia; & Marchetti, Damiano. (Producers). (2017, December 15). #112: The prophet. Reply All. [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from https://www.gimletmedia.com/reply-all/112-the-prophet

Trice, Michael & Potts, Liza. (2018). Building dark patterns into platforms: How GamerGate perturbed Twitter’s user experience. Present Tense, 6(3). Retrieved from https://www.presenttensejournal.org/volume-6/building-dark-patterns-into-platforms-how-gamergate-perturbed-twitters-user-experience/

1 Comment

When I first started your story–which is great– I was trying to figure out when the initial incident took place so I could place it into a wider context. Eventually the time period is revealed when talking about the Pena Nieto election campaign. But, it would be nice to have that up front, although it is a common practice.