There is something profoundly democratic about a bathroom stall. No velvet rope, no blue check, no institutional imprimatur—not even a username. Just a flat surface, a stylus, and the uncorked bile of a writer who neither sought nor needed your permission. And while many a self-serious theorist has long since baptized digital platforms as the new agora, I submit for your approval a more humble counter-public: the wall; scratched, scribbled, and sprayed with the analog palimpsests of modern discontent.

Since the digital turn, rhetorical scholars have fallen over themselves to theorize the tweet, the meme, the post, the endless scroll. Circulation, they proclaim, is the province of retweets and algorithms—of platformed texts that “go viral.” This dogmatic digitalism, while fashionable, is blinkered to the point of monomania. And it’s time we name the problem: when rhetorical circulation is mostly theorized through digital channels, we don’t just narrow the scope of inquiry—we misunderstand the phenomenon itself.

To be clear, rhetorical circulation has always existed. Before the tweet, the pamphlet. Before the meme, the mural. Before the thread, the wall. And before the comment section, the stall. If rhetorical meaning emerges through the movement of texts across publics, we shouldn’t pretend this process was invented when Mark Zuckerberg discovered PHP.

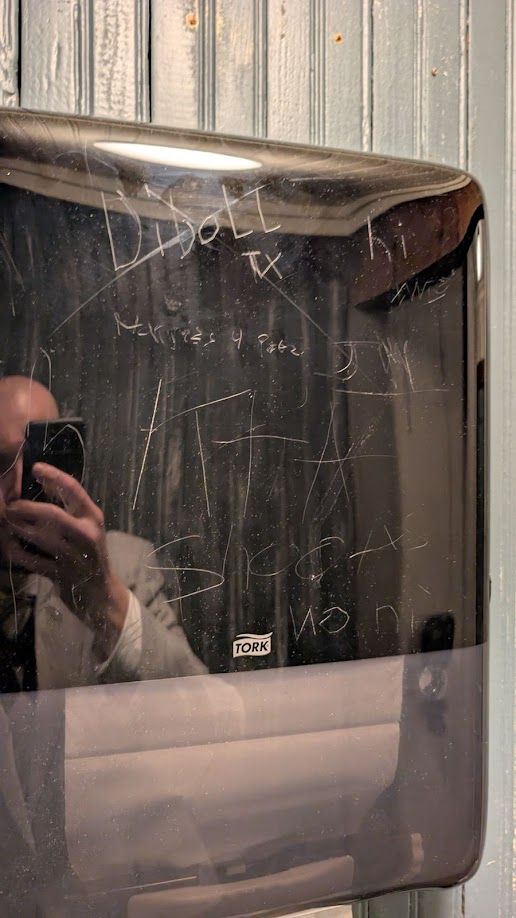

Take latrinalia, or, as it’s more commonly known, bathroom graffiti—that most subterranean of subgenres. My research (Marine, 2023a; Marine et al., 2021) has traced its rhythms and rhetoric across the tiled walls of a large public university. What emerges is not “mere graffiti,” but a recursive, evolving conversation of public rhetors who pass through the same space but not at the same time. A student writes “Trump is a moron”; another scrawls over “moron” to write “genius”; a third adds “When?”—a primitive form of quote-tweeting, if ever there was one.

And yet the darlings of rhetorical circulation theory—and those who chant their names like an incantation before every mic check at the Cs—seem obstinately committed to ignoring this fact. They nod toward materiality, maybe even cite Still Life with Rhetoric, and then pivot right back to the screen. As if circulation only counts when a platform can track it. As if offline discourse were a quaint but outdated curiosity.

To be plain, this overfocus on the digital doesn’t just narrow the aperture of rhetorical inquiry but distorts it. Rhetorical circulation happens offline, often with more intimacy, risk, and contextual weight than what trends online. A graffito gains momentum not through algorithmic velocity but through spatial embeddedness. Its audience is hyperlocal, its risks tangible. Its circulation isn’t viral in scale, but viral in structure: slow, infectious, and rooted in lived, material experience.

As Eyman (2007) reminds us, texts become rhetorical as they move—decoupled from original contexts, remixed into new ones. That’s not a feature of Twitter; it’s a feature of rhetoric. Gries calls rhetoric an “unfolding event,” whose meaning actualizes over time and space. Fine. But what, then, is an ongoing, multimodal, multi-authored graffiti conversation if not an unfolding event? What is a graffito in a bathroom stall, revisited and revised across semesters, if not a living artifact whose rhetorical effects exceed intention and authorship, gathering momentum like one of Gries’s precious tumbleweeds—only this one doesn’t need a windswept plain or a metaphorical mood board to matter.

This is not an argument for rejecting the digital. Far from it. The digital is a rich, evolving domain of rhetorical action, and scholars like Gries have done much to illuminate its complexity. But so too is the analog, which remains deeply interconnected with the digital through processes of remediation, adaptation, and recontextualization. Today’s graffitists often photograph their work, upload it, share it—remediating analog text directly into digital life. Conversely, digital texts bleed into the physical: QR codes, stickers, stencils, chalked slogans. We are living in an age of recursive circulation where rhetoric bounces back and forth across the analog-digital divide, blurring the line ever more with every pass. My point is that it is this recursive movement itself—how rhetoric transforms as it shifts mediums and contexts—which demands closer study as a (if not the) defining dynamic of contemporary rhetorical life.

Pedagogically, this iterative interplay matters. As I’ve argued elsewhere (Marine, 2023b), latrinalia is not just a curiosity but a site of learning. It surfaces suppressed rhetorics, reflects student sentiment, and invites us to reconsider the spaces and places in which writing instruction happens. The most rhetorically impactful writing on campus may not be composed in the classroom, but on the walls just outside it. And if we’re serious about studying circulation, we must pry our eyes from the screen long enough to see what’s been inscribed right in front of us.

Of course, the supposed democracy of the bathroom stall is far from absolute. Restrooms remain some of the most regulated and contested public spaces—structured by gender, surveilled by policy, policed by perception. Yet it’s precisely this entanglement that makes latrinalia so rhetorically rich. It is one of the only forms of writing that unfolds in overtly gendered spaces, and that alone should draw the attention of a field allegedly preoccupied with power, access, and the politics of voice. That graffiti continues to circulate in these fraught zones—often anonymously, often subversively—ought to make it a prime object of study, not a marginal curiosity relegated to the fringes of rhetorical inquiry. But perhaps that would require stepping away from theory long enough to confront rhetoric where it’s least curated, least sanitized, and most alive.

The analog, in short, is not inert. It is not pre-digital. And it is not less sophisticated. It circulates. It interanimates. It incarnates. And it constructs publics and provokes responses grounded in the material realities of human experience without the muffling filters, algorithmic gauze, and antiseptic screens (not to mention, bots) that neuter, deaden, and drain the life from so much digital discourse. In this way, analog rhetorics like graffiti are perhaps the most vivid and visceral manifestations of the very theories digital scholars apply to social media with such feverish, myopic delight. To ignore this fact is to elide half the rhetorical ecosystem. To pretend rhetorical circulation was born in a hashtag is to confuse the interface with the infrastructure.

Sometimes, the most rhetorically potent texts are the ones no one meant for you to read. Sometimes digital circulation begins where the Wi-Fi ends—on the wall, on the stall, in plain view of us all.

References:

Eyman, Douglas. “Digital, Rhetoric: Ecologies and Economies of Circulation.” Unpublished dissertation. Michigan State University, 2007.

Gries, Laurie. Still Life with Rhetoric: A New Materialist Approach for Visual Rhetorics. UP of Colorado, 2015.

Gries, Laurie, and Collin Gifford Brooke, eds. Circulation, Writing, and Rhetoric. UP of Colorado, 2018.

Marine, J.M. (2023). “Analog to Digital and Back Again: The Rhetoric of Graffitti.” Rhetoric Review, 43(4), pp. 286-303.

Marine, J.M. (2023). “Mere Graffiti: The Pedagogical Implications—and Potential—of Latrinalia Research.” Reflections: A Journal of Community-Engaged Writing and Rhetoric, 22(2): pp. 118-151.

Marine, J., Biller, B., Tuckley, L. (2021). Divided Discourse: Establishing a Methods-Centered Approach to Latrinalia Research. Discourse Studies, 23(3): 265-287.