Though I’ve been teaching students about filter bubbles for a few years now, the topic has gained visibility after the election. SNL had its skit poking fun at “The Bubble” of progressives escaping the election’s reality, and The Wall Street Journal‘s Red Feed, Blue Feed simulates the polarization of our political spectrum through model feeds. Pariser’s term-coining book came out almost six years ago, but in the current political climate, filter bubbles warrant renewed attention.

In this post, then, I want to describe how I’ve started discussing filter bubbles after the election, focusing on a particular activity from my research writing class while also situating that activity within class readings. And though this is from a class on research-intensive writing, I imagine that writing classes on technology, ethics, politics, or the media may also have something to glean from the activity.

In general, I emphasize the role of authorial curation in filter bubbles—how these “bubbles” don’t exist accidentally but have deeper logics and larger implications beyond them.

Introducing the Topic

In terms of readings, I tend to start with Eli Pariser’s TED talk on filter bubbles, often linking students to Maria Papova’s interview with Pariser to give them more to work with. This talk introduces the concept and a few terms, like algorithmic curation and “media diet.”

I often pair Pariser’s talk with Daniel Estrada’s “You Are Your Bubble,” which critiques discussions of the filter bubble. Such discussions, Estrada argues, tend to blame individual users, asking them to vary their media diet, as Pariser does, or “pierce” the bubble. Many solutions also involve Facebook “sprinkling the stream with opposing perspectives” or imposing labeling and screening, which do not fix many of the underlying problems. Instead, Estrada argues that we should recognize the bubble as an extension of our identity and learn to “own it.”

I also like to connect these readings to more general readings about bias, drawing from David McRaney’s You Are Not So Smart blog, like his posts on confirmation bias and the backfire effect. In addition to bias, I may also discuss or assign readings on the attention economy and trending, like Eunsong Kim’s “The Politics of Trending” or work by danah boyd. And more recently, I’ve grounded these discussions within our divisive political climate, as this video from “The Good Stuff” points to.

The Daily Brief

With some general concepts in place, often fortified through class discussion, we do activities. For this particular post, I’ll focus on one: the daily brief.

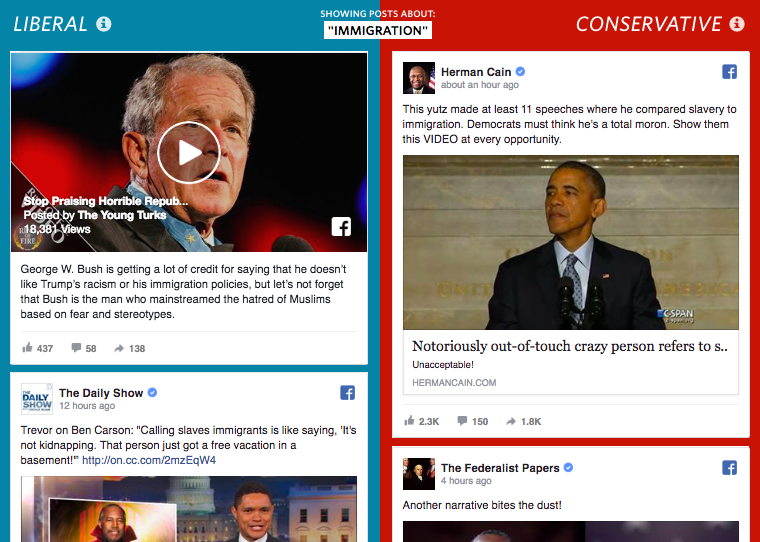

For this, groups construct a political “daily brief” of the top five political news stories for the day, like the New York Times or the Associated Press does, but each group can only use certain collections of sources, simulating a filter bubble. For “conservative” groups, I limit them to sites like Townhall, Drudge Report, the Geller Report, RedState, and The Daily Caller, though I may shift up these lists. For “liberal” groups, I may use US Uncut, The Raw Story, Occupy Democrats, Huffington Post, and AlterNet. I then have a control group that draws from more traditional sources, like CBS, CNN, NBC, and ABC. I recognize the somewhat arbitrary nature of these picks, which I got looking at a few sources, like the Pew, but the main thing is curating a restricted pool, simulating a bubble.

On separate Google Docs, each group distills the sources into briefings and collects a few representative articles. For homework, they then review the briefings and representative articles and compare them in a low-stakes writing assignment asking the following questions:

- Where do the briefings overlap? Which stories seem confined to individual bubbles?

- How do sides view these overlapping stories?

- How do the sources speak to audience identity? How do you know?

- How would we characterize the tone or feeling of these sources?

- What sort of information do they draw from—interviews, studies, unnamed sources, etc.? How do they link to other sources or stories?

- What standards of credibility or accuracy seem to exist in each bubble? How do you know?

- Do particular key words keep coming up overall? Within each bubble?

- What sort of worldview(s) exist among and within these bubbles?

In the next class, with this writing as a reference, we talk about these questions and related questions regarding the attention economy, audience, and the link between political ideology and news.

From here, I have individual students, freed from their imposed filter bubbles, construct two daily briefs for a final writing assignment: one for them and one for a more general audience. They also must explain their reasoning for each brief—why these sources and not others—as if it were a set of rules or algorithms. For example, should the briefing bring in sources from other bubbles? What criteria do you use to pick sources? This particular assignment could likely build to a larger project regarding source evaluation and audience.

Conclusions

In terms of pedagogy, filter bubbles help address source evaluation or algorithmic curation. But, like anything connected to writing and rhetoric, filter bubbles also have larger social and cultural implications—particularly in light of this election.

Our self is networked, online and off, with that network influencing our terministic screens, as Burke might put it. And as students encounter polarized pools of sources, they often recognize the gaps between perceived political “realities.” Having to work with(in) these bubbles to construct the daily brief, they witness the recursive links between information and ideology—as well as the often unacknowledged responsibility of curation. Doing so, I hope, gives students a more reflexive reference frame when engaging with politics, more agency in directing their bubbled self, and a stronger sense of the relationship between social media and politics.