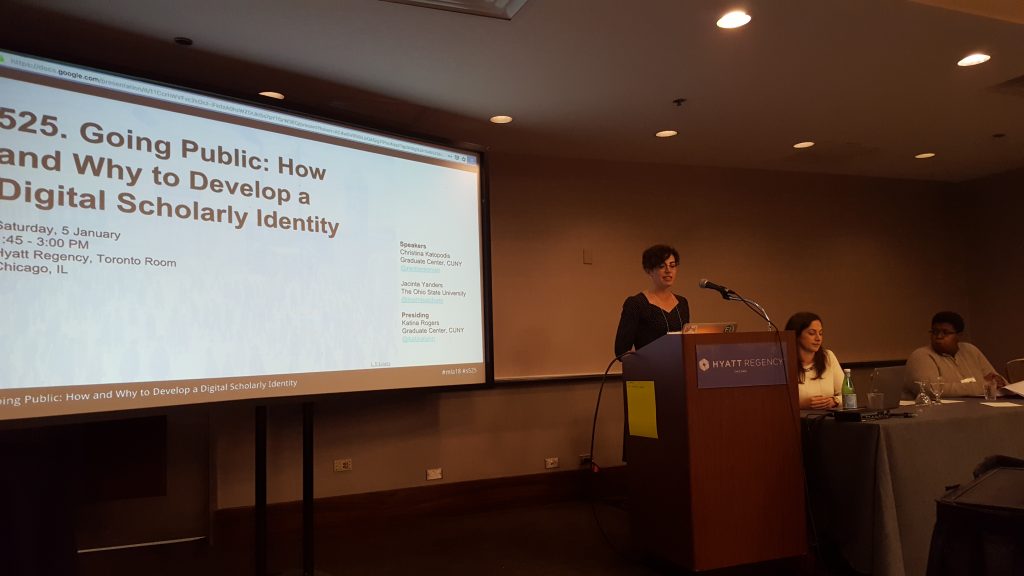

Presiding: Katina Rogers, Graduate Center, CUNY, @katinelynn

Speakers: Jacinta Yanders, The Ohio State University, @learnteachwin; Christina Katopodis, Graduate Center, CUNY, @nemersonian

If you’re here, you have a presence online. So began Katina Rogers’ opening remarks in the workshop she, Christina Katopodis, and Jacinta Yanders hosted on digital scholarly identity. As they argue, it is impossible today not to have a presence online: your name might appear in the program of your national association conference, you might be tagged in an old photo or youthful digital escapade, or your students might have created a profile for you on RateMyProfessor.com. As modern day scholars, we cannot avoid an online presence. What we can do is control what that presence looks like and what it says about us—and this is the subject of the workshop. Responding to the MLA 2019 theme of Textual Transaction, the workshop takes up the call to this question about the transactions between human, text, and context by asking participants to think about transaction in the construction of a digital scholarly identity: both the required transaction between scholar and public of having such as identity and the online transactions necessary to create one. Designed as a discussion between the panelists, the workshop offers only brief notes from each panelist followed by a more Q&A-style discussion, so in this review I focus on highlighting the themes of the workshop.

Risks of Digital Scholarly Identities and Work

As part of their remarks, speakers Katopodis and Yanders highlight both the risks of a digital presence and the rewards, themes which carry through the rest of the workshop. They begin with a think-pair-share activity, asking attendees to list one thing that scares us about having a digital identity and one thing that excites us. Here are the fears we shared:

- judgement by other scholars/people in field;

- theft of our work and ideas;

- data security and being hacked;

- data management as the complexities therein;

- harassment and trolling;

- time and affective costs of being on social media more

Speaking to an audience that includes both scholars with active or burgeoning online presences interested in learning more and those skeptical of the entire endeavour, all the three panelists refuse to shy away from the tangible risks and efforts of digital identities and digital scholarly work, acknowledging the concerns of participants and sharing their own experiences: the harassment, the affective costs, the sometimes-steep technological learning curves, and the time required. Their workshop focuses not on setting aside these concerns but productively working within them.

Rewards of Digital Scholarly Identities and Work

So why have a digital scholarly identity?

Yanders, an active blogger and participant on Twitter, acknowledges the risks, but argues that we shouldn’t necessarily avoid posting online as a result. For Katopodis, it’s about balance: knowing the risks and what we’re comfortable with, and then choosing our online participation appropriately. As Rogers argues in her opening remarks, taking control of our unavoidable digital presence can help us shape it so it reflects the parts of us we want to reflect. Having a digital presence that we control—our own social media profiles, our own websites and/or blogs, academic profiles on MLA Commons, and LinkedIn and Google Scholar—means that we can control some of our representation online. And there are, as all three speakers highlight, a great number of benefits to participating online: connecting with scholars around the world; building communities; using material from online spaces in your academic work; connecting with opportunities for work, publication, and mentoring; getting access to resources like syllabi and conversations in your field; and more.

Focusing on these benefits, all three speakers demonstrate that the rewards of digital scholarly identities are worth the risks and work. By sharing their own experiences—Yanders shared a particularly exciting one about Twitter facilitating connections that lead to her interviewing people from the TV show Wynona Earp for an article—the speakers argued that while digital identities are hard to build and there are risks, they also enable opportunities that would be impossible elsewhere.

Takeaways

So how can academics go about creating a digital identity as a scholar?

The panelists advice on this question is both philosophical and practical:

1. Build a Digital Identity with Purpose

Rogers, Katopodis, and Yanders all recommend that academics think critically about what their goals are for their digital identity, what their level of comfort is with various technologies and engagement options, and how comfortable they are with the risks of participation online. With these goals in mind, academics can tailor their participation to their own needs and comforts. Not comfortable with the open publics and potential for harassment on Twitter? Consider MLA Commons and Hastac as more scholarly focused spaces that still have considerable weight in Google’s search algorithms.

2. Start Small

You don’t have to do everything online, and you don’t have to do everything at once. Yanders recommends picking one platform to work on then, once you’re comfortable with that platform, adding another space. Rogers recommends beginning with an inventory of your social media activity to think about what you do know and how much time/effort you want to dedicate. Katopodis emphasizes that there are different levels of participation from establishing a relatively static profile (LinkedIn, Google Scholar, MLA Commons) to active and frequency participation such as Twitter and blogging; she emphasizes that you can choose what’s right for you.

3. It’s About What You Give

For Katopodis, the #1 rule of online participation is, “It’s not about what you get! It’s about what you give.” When establishing an online digital presence, Rogers, Katopodis, and Yanders all think about their participation in terms of giving: sharing experiences on a regular teaching blog, sharing perspectives by participating in conversations in the field, sharing digital skills through mentoring or advice. They argue that while digital spaces have a lot of potential to give us opportunities, that doesn’t happen without us first giving our time, attention, and participation to digital communities.

To sum up their advice: A digital scholarly identity is a powerful tool for self-expression and community. Successfully building a scholarly identity requires thinking about how and why you are going online.