Katharine Hayhoe has impressive academic credentials. As a climate scientist, she has 125 peer-reviewed publications and serves as director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University. Hayhoe is also an excellent public communicator.

Much of Hayhoe’s climate advocacy work happens in non-academic online spaces: Quora, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter. Hayhoe also identifies as an evangelical Christian and is known for her ability to convince fellow believers to take action.

I am fascinated by Hayhoe’s ability to present herself not only as an accomplished scientist but also as a woman, a Canadian, and a believer. For communicators interested in digital advocacy, Hayhoe’s social media rhetoric is a clear model for creating an embodied, persuasive ethos online, in ways that make her climate advocacy stick.

Ethos is commonly understood as an “artistic proof” (Colton and Holmes 2018): a writer presents a version of herself which looks credible to her public, but which may or may not bear any relation to her real self.

But ethos is more complex than that. Ethos includes a writer’s “standpoint” (Jarrett and Reynolds 1994) or habitus, the “places from which [she]speaks” (52) that make her worth listening to. As writers speak from their lived experiences, they gain credibility, often even among resistant audiences.

The notion of ethos as standpoint is especially relevant to digital advocacy.

Collin Brooke (2009) writes that online, ethos is no longer reducible to quantifiable metrics, such as Hayhoe’s employment as a tenured climate scientist at a research university, or her 125 peer-reviewed papers.

While Brooke’s analysis of pseudonymous academic blogs makes clear that ethos may exist without a “traceable connection to the ‘real world’” (184), other theorists such as Kristie Fleckenstein suggest that digital ethos may also arise out of the recursive, looping interaction between one’s material and virtual realities.

Drawing on cybernetics, Fleckenstein (2005) envisions ethos not as a discrete quality a writer carries into the discursive situation but as a dynamic series of relationships among place, audience, and the speaker’s virtual and material realities. The interaction among these relationships generates ethos. Ethos online is the nexus between a writer and her publics, and between her online identities and her material, embodied self.

Put another way, ethos online is less a standpoint than standpoints, as a writer’s virtual and embodied realities, and the realities her audience inhabits, connect in ways that make space for the writer’s voice to be heard as persuasive.

What this means is that it is the interplay between Hayhoe’s digital self-presentation and the embodied realities which she shares with her readers that lends her climate advocacy ethos. The design of her rhetoric invites readers to see climate change action as belonging to spaces they already inhabit, such as their faith or nationality, and enables Hayhoe to advocate more persuasively for environmental responsibility.

Both Hayhoe’s YouTube series Global Weirding and her use of Twitter exemplify this design, bringing together Hayhoe’s scientific expertise and her embodied realities to make her advocacy persuasive.

Ethos on YouTube

“Oh Canada,” part of a series on debunking common climate myths and urging action, documents Canada’s outsized contribution to carbon production and motivates Canadians to change.

Hayhoe portrays herself in the video as approachable. She is dressed not in a suit but in a black blouse and is wearing her hair down. Looking the viewer directly in the eye, she seems to erase the distance(s) implicit in online communication. Hayhoe’s material identity is thus projected into her virtual identity so that viewers experience her presentation as open, honest, and “real.”

Among the material identities Hayhoe claims in this video is, importantly, her Canadian identity. She names the video after Canada’s national anthem, empathizes with Canadians’ longing for warmer weather, and shares Canada-specific climate data. Hayhoe urges her fellow Canadians to step up: “If you’re Canadian like me, you have proportionally more to do to” reduce climate change; the first-person plural links Hayhoe to her readers: their climate change responsibilities are her climate change responsibilities.

A more static model of ethos might point out that Hayhoe’s claiming of her Canadian identity invites Canadian viewers to trust her. That’s true.

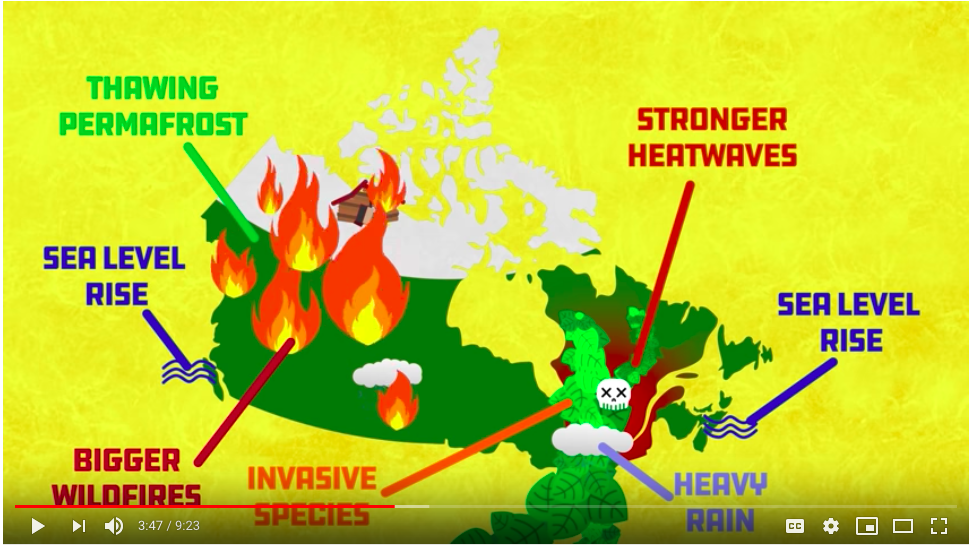

But it’s also true that Hayhoe is reworking that Canadian identity in important ways. On YouTube, the Canadian identity she projects goes hand-in-hand with her identity as a climate scientist. She also takes up familiar aspects of Canadian identity, such as its map, and overlays them with key climate change information:

The video thus becomes a site for reimagining what it means to be Canadian. Recalling Fleckenstein’s description of ethos as the interaction among a writer, her publics, and the material and virtual spaces they inhabit, the video’s design locates care for the environment as an integral part of Canadian identity. In so doing, it persuasively invites viewers to inhabit this new, renovated understanding of their national identity, as Hayhoe herself does. In this way, Hayhoe’s bringing together of her Canadianness with her commitment to climate action points up the relational nature of ethos online–in particular, the need for a writer to inhabit the same space(s) as readers, in order to reinvent those spaces in persuasive ways.

Ethos on Twitter

Similarly, in this tweet, Hayhoe claims her Christian identity to reimagine “being Christian” in a way that includes taking responsibility for climate change:

The arched windows in the tweeted photo recall a medieval cathedral, while the words projected on the wall–“the overwhelming, never-ending, reckless love of God”–explicitly write this place as religious. Hayhoe uses this image to situate herself within long-standing evangelical heritage.

Yet the image, captioned “talking climate faith and love,” is from her talk at this church about climate change. Such a talk is different from the kind of talks usually given in a religious space such as the one pictured, so that the caption rewrites the space that Hayhoe and her evangelical publics inhabit as one that remains rooted in Christian practices, while at the same time opening up the space for learning about and taking action on climate change. The caption functions as an “imageword” (Fleckenstein 2007), with Hayhoe’s caption inviting her viewers to experience their familiar religious spaces in a different way, as a place that motivates climate action rather than resisting it.

As with “Oh Canada,” Hayhoe is digitally rewriting her own embodied ways of being. She moves fluidly among her climate scientist identity, her viewers’ evangelical identity, and her own evangelical identity, remaking the religious spaces she inhabits with her readers into spaces that make environmental responsibility possible.

The ethos generated out of Hayhoe’s fluid, multiple habituation(s) encourages those similarly engaged in digital advocacy work to consider how they may indwell and transform the space(s) they share with their publics.

Pedagogical Implications

In fact, Hayhoe’s work provides a strong model for students engaging in digital advocacy. Specifically, teachers designing digital advocacy projects may consider how their students will establish ethos by asking the following questions:

How do students “project” their identity on-screen?

Will students appear in person at all? If so, will they make eye contact? What position(s) will they take in images, videos, or VR space, relative to viewers? How will they use fashion choice, graphics, and sound to enact their material realities on-screen? Answering these questions help students choose an identity that relates their embodied being to their virtual one in persuasive ways.

How do students’ lived experiences relate to the audience’s, and to the place(s) both inhabit?

As Hayhoe demonstrates, projecting a particular persona is not enough; students need to think about how their lived realities interact with the audiences’ lived realities, and with the spaces that both inhabit. How will students use multimodal writing to locate their work in particular place(s) and “see” those places in new ways, as Hayhoe “sees” the church as a place open to talking and acting on climate change? How will students use multimodal writing to differentiate their ways of being from their audience’s ways of being?

Ultimately, as students (or teachers) answer these questions, they design an ethos that makes their digital advocacy convincing. As digital projects invoke the embodied realities which writers and readers inhabit, those realities are transformed in meaningful, persuasive ways that invite even hesitant publics to act.

References

Brooke, Collin Gifford. Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media, 2009.

Colton, Jared S. and Steve Holmes. Rhetoric, Technology, and the Virtues, 2018.

Fleckenstein, Kristie S. “Between Perception and Articulation: Imageword and a Compassionate Place,” In The Locations of Composition, ed. Christopher J. Keller and Christian R. Weisser, 2007, pp. 151-170.

–. “Cybernetics, Ethos, and Ethics: The Plight of the Bread-and-Butter-Fly.” JAC, 25.2 (2005) pp. 323-346, https://www.jstor.org/stable/20866692

Hayhoe, Katharine. “Oh Canada,” YouTube, uploaded by Global Weirding with Katharine Hayhoe, 20 February 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pr1LzjXbqR0

@KHayhoe. “Talking climate faith and love at @grace_capital tonight in DC,” Twitter, 16 Dec 2018, 2.37 PM, https://twitter.com/KHayhoe/status/1074433292068360192

Jarrett, Susan C. and Nedra Reynolds. “The Splitting Image: Contemporary Feminisms and the Ethics of ethos.” In Ethos: New Essays in Rhetorical and Critical Theory, edited by James S. Baumlin and Tita French Baumlin, Southern Methodist UP, 1994, pp. 37-64

Macarthy, Frank. “Digitizing Material Bodies,” Prezi, uploaded 14 March 2019, https://prezi.com/su34uy4805j3/digitizing-material-bodies/.